“What an Electric Mixer can do to make light work of your kitchen chores”

Design historian Alice Naylor takes a look at how food mixers and refrigerators were presented in Good Housekeeping magazine in the 1950s.

The popular thinking in the discourse of household management in the first quarter of the twentieth century was to propose the kitchen as a factory in the home. Household appliances such as vacuum cleaners and food mixers were designed to bear a close resemblance to factory tools that hinted at efficiency. They were frequently advertised in print media including magazines aimed at female readers because manufacturers understood that they represented a key audience for labour saving devices.

Good Housekeeping magazine was an influential publication for middle-class women: a source of advice and information for housewives on matters relating to the home. The kitchen was perceived, certainly in the context of normative idea of womanhood, as the space where the housewife could express her personality.

The multitude of consumer durables on offer required an elegantly designed kitchen to best showcase the modern and stylish appliances acquired by the fashion-conscious and socially aware housewife. Kitchens and kitchen appliances were regularly featured in the advice columns and advertisements for equipment were placed throughout the magazine.

By the 1950s, the electric food mixer was a recognisable addition to the housewife’s kitchen toolkit.

Electric food mixers were not unfamiliar to the British housewife by 1950. Versions had existed since the early 1930s to enable more efficient food preparation. However, at this point, food mixers did not follow the styling adopted in refrigerator and cooker design. It was common for these consumer durables to mimic the look of American automobiles with glossy cream paintwork and shiny chrome fittings.

With their affluent readers in mind, Good Housekeeping made a case for the advantages of this device highlighting it as essential to the modern home as a vacuum cleaner or washing machine. It was, the magazine believed, an invaluable part of the domestic appliance repertoire: no longer a luxury but a necessity. The cost ranged from £15.00 to £30.00. It is understandable that the electric mixer may well have been seen as a luxury, despite Good Housekeeping suggesting otherwise. In 1950, £15.00 was the equivalent of £468.00 in today’s prices.

The mixers featured in this October 1950 editorial came at a significant date for this kitchen appliance. In March 1950, the Kenwood Electric Chef was introduced to consumers at the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition at London’s Olympia. Good Housekeeping‘s May edition of the same year ran a small advertisement declaring it ‘a Chef for every home’.

“a Chef for every home”

Advertisement from Good Housekeeping, December 1951

What made the Kenwood Chef stand out? The primary selling point was that it would save the housewife time. It would help with making cakes, whisking cream, mincing meat and, in the case of the Kenwood mixer, liquidising fruit and grinding coffee. What is significant for design historians and those with an interest in the look of postwar kitchen appliances, is the way that this British version of a food mixer was styled.

This black-and-white image depicts an elegant, if somewhat oblique-looking mechanised object. It is far removed from the factory-tool aesthetic of its predecessors and at a glance, viewers might mistake it for something other than a kitchen appliance. The removable goblet attachment perched on the top of the Chef was made from heavyweight glass and its ziggurat-style profile was reminiscent of an earlier art deco styling.

In tribute to the American automobile styles present in many small domestic appliances in the mid-1940s, it was finished in glossy cream paintwork with glistening aluminium fixings. It is worth noting that the strapline ‘A Chef for every home’ was an attempt, and ultimately a highly successful one, to portray this device as an attainable way to acquire your own personal Chef.

the impact of the Festival of Britain

A significant cultural and social milestone that came to define the British public’s attitude to home interiors was the Festival of Britain. This impact was conveyed to consumers in different ways. Editorials and advertisements in newspapers and magazines enabled consumers to take the inspiration and ideas presented in the Festival of Britain and realise them in their own homes. The kitchen was where profound cultural and social changes were taking place. Women, and crucially housewives, were at the centre of this revolution.

It was common for advertisements in consumer periodicals during interwar and postwar Britain to depict women in the home as an idealised version of the housewife. Housewifery was framed as a ‘profession’ by the Government and media which placed women at the heart of home management. This essential, albeit unpaid, role was part of an ongoing discourse around nation-building. The housewife was seen as critical to the creation of a happy and productive home life.

Refrigerators reveal social change

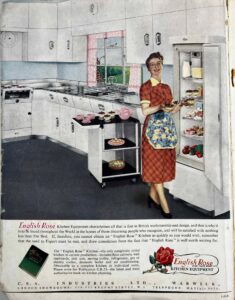

The ‘English Rose’ kitchen advertised on the opening page of the December 1951 issue of Good Housekeeping is an example of the pre-fabricated model designed with the modern housewife in mind. That is, a panoply of consumer goods and integrated storage systems to enable the efficient running of the kitchen. The units, the electric cooker and the refrigerator are dazzling white whilst vivid reds, pinks, greens and yellow emphasise the luscious cooking ingredients displayed alongside her.

‘English Rose’ kitchen advertisement, December 1951 issue of Good Housekeeping

Historians of technology, design and feminist history have noted how consumer durables such as refrigerators reveal social and cultural changes in domestic life. The kitchen is where traditional responsibilities for feeding and caring for the family are played out with the refrigerator being an example of an appliance that was seen as becoming as necessary as a cooker or a vacuum cleaner.

By the 1950s the refrigerator was seen as both a status symbol and a necessity. Historian Helen Watkins makes the point that refrigerator advertisements implied that inside lay a ‘lush food landscape’ that was ‘magically replenished’ to be gazed and grazed upon’ (Watkins, H., 2006. Beauty queen, bulletin board and browser: Rescripting the refrigerator. Gender, Place & Culture, 13(2), pp.143-152, p.146). She makes the point that the re-stocking of the refrigerator would fall to the housewife and it is evident from the image we see here.

Both housewife and her sumptuously stocked refrigerator are at the forefront of this image. She is dressed in the fashionable clothing of the day; a slim, mid-length dress and high-heeled shoes part covered by a floral apron. The apron is a visual reminder that she is some way, connected to the practice of cooking. The refrigerator is equally fashionably attired although its contents, like the housewife, are somewhat of a fantasy. Food rationing did not cease until 1954 and therefore the butter, meat, cream and pastries portrayed in this advertisement were far from everyday items for the majority of British households. It is significant that the housewife and her elegant refrigerator are the key features here.