In 1930s Britain, women across the class spectrum were encouraged to cultivate their bodies in the pursuit of health and fitness. Athleticism came to represent a “civic virtue”, and physically active women were celebrated as modern (Zweiniger-Bargielowska 2011, 299). Some historians have argued that this also opened new job opportunities for women through sports culture, challenging nineteenth-century tropes of “the eternally wounded woman” and providing more chances for mixed-sex sociability (301).

The Modern Woman raises questions regarding the ‘duty-to-beauty’ through physical exercise. Was it liberating? What ends did it serve? What relationship does it establish between physical and mental health? And how might that link to contemporary debates about our bodies?

As you read, here are some questions to think about

- Women’s cultivation of the body and beauty culture has been interpreted in some contexts as narcissistic and shallow. To what extent to you agree or disagree with this?

- As women undertook exercise and sports they also claimed a space for their bodies in public life. How far do you think this changed their life opportunities?

- Do you exercise? How is that related to your sense of self? And wellbeing?

The Modern Woman (1936)

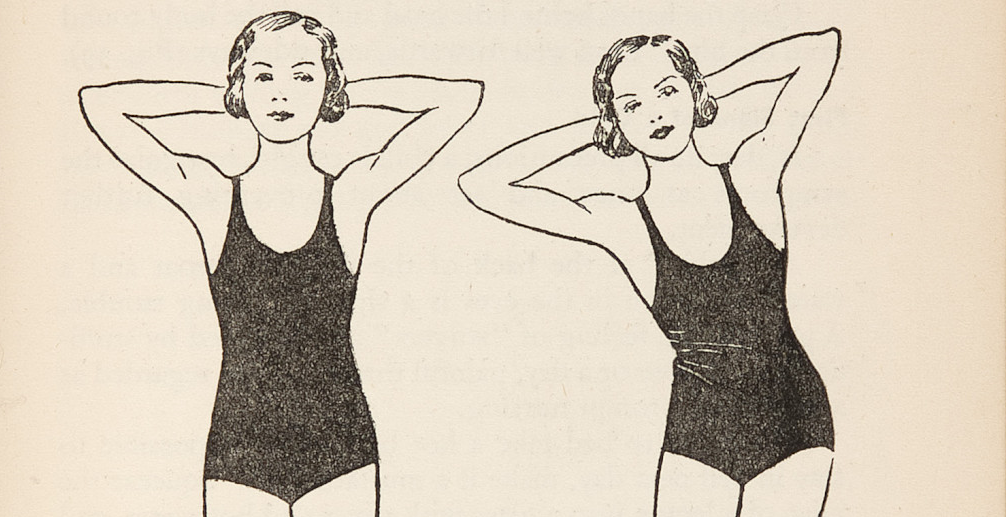

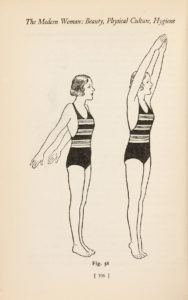

The book advises ‘modern women’ to follow a daily beauty routine based on the “right diet, exercise, cleanliness and health”  (Zweiniger-Bargielowska 2011, 302):

(Zweiniger-Bargielowska 2011, 302):

“Beauty must not seek to cover up her defects but to eradicate them. […] The first steps to natural health and the foundation of beauty are, therefore, sleep, diet and correct elimination.” (p. 2)

The passages contain instructions for women of different age groups, including what to eat, how much, what exercises are beneficial to avoid the ageing, how to keep a healthy skin, etc. It also advises women to find their “type”, whether it is brunette, blonde, or auburn. The association of health with women’s physical attractiveness reinforced ideas about her duty as a “race mother” who would “cultivate her body for the well-being of the nation” (Zweiniger-Bargielowska 2011, 313).

The book also makes a link between physical health and “inner beauty”:

“Women are taking more and more interest in their looks, but this time there is a difference. Women have realized that to be beautiful without, they must be healthy within.” (p. 1)

This matched growing concerns at the time about the population’s health. It was not unusual for commentators to make connections between body and mind: ‘outer vitality’ depended on ‘inner radiance’ (Macdonald 2013, 267). This suggests that discourses about the body were part of a bigger “self-making” endeavour: being healthy and active could inform one’s sense of self and provide a guide to living in the modern world (275).

Extracts from the book...

Find out what else has been written about this by looking at our reading list