The fully wired home and the modern consumer

PhD student, Alice Naylor gives us an insight into the adoption of electricity into British homes between the 1930s and 1950s. Alice’s research mainly focusses on the history of the Kenwood Chef. But to understand how Kenwood Chefs were adopted by British consumers, she first had to understand more about the supply of electricity.

Electricity in British homes

In 1932, only 32% of British households were wired for electricity, rising to 65% in 1951. The electricity industry was nationalised in1947. This enabled many more homes to access this energy supply easily and cheaply.

Many homes were fully wired prior to the nationalisation of the electric grid. But it was after World War II that electricity was widely accepted as the norm in houses rather than an afterthought. What had previously been a somewhat patchy system of supply was becoming more commonplace and efficient. Heating and lighting were the most immediate ways in which households could benefit from a fully wired home.

There was an imperative to build new homes in the aftermath of World War II which had resulted in critically low housing stock. Architects and housebuilders ensured that electricity supplies were configured into the overall layout of new homes. For example, pre-fabricated houses were built to accommodate the many ways in which electricity was incorporated into everyday life.

Significant social, cultural and political changes and rising standards of living saw shifting patterns of domesticity and an emphasis on family life. With a consumer focus on the home, higher wages, and an increased demand for electric-powered appliances, households, and housewives, were alerted to the benefits of electricity.

Heating the Home with electricity

Electrical heating was not uncommon in the 1930s, but the cost was too high to allow most consumers to heat the entire house. In fact, central heating was not widely adopted until well into the late 1960s. In the 1930s, portable electric heaters offered an economic solution for heating rooms as needed, and could be installed in bedrooms that were less likely to have an open fireplace.

The fireplace was the practical and symbolic heart of the home and many people relied on open coal fires to heat the sitting room where the family would gather. This method may have been relatively cost-effective but the coal had to be brought into the house, the fire laid, lit and sustained, most often by the housewife. It was a laborious and messy process.

frontispiece from Ourselves and our Homes, 1951 Winifred Burman

The image from 1951, depicts a family in front of their traditional coal fire. This practical economy may have enabled them to make more strategic use of their energy supplies.

The family’s living room appears to be wired to accommodate the floor lamp to the left of the fireplace and a radio behind. Lighting and leisure were often the ways in which families rationalised the cost of their electricity bills.

Whilst electric fires were commonplace from the 1930s onwards, they were fairly functional and designed to sit inside an existing fire surround or as a stand-alone device.

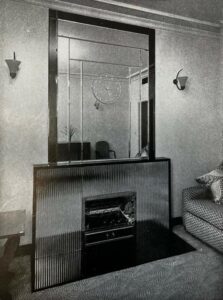

Designer: W.Curtis Green, R.A. (p.31)

By the 1950s, the living areas of the home were refashioned to accommodate changing domestic habits and an increasing array of electric-powered appliances.

Heating systems like the fireplace, particularly for affluent households were designed to reflect a modern and fashionable lifestyle. It was a central gathering point not just for families listening to the radio or watching television but hosting social gatherings in stylish surroundings.

The image here depicts an elegant model with a rippled glass surround and an impressive mirror above the overmantel. The main purpose of this fireplace appears to be an eye-catching focus for the living room, not simply a heating solution. The reflective qualities of the light and the elaborate mirror are presented as decorative additions for redefining an awkward space.

Electricity in the kitchen

In pre and post-war Britain, the kitchen was seen as the working centre of the home. Between the 1920s and the late 1940s the layout of the kitchen was considered more important than its interior design. Influential publications such as The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home-management by Christine Frederick (1914), had a long-lasting impact on the design of kitchens. This recommended a layout that enabled the housewife to move around the kitchen efficiently to expend as little energy as possible.

Less attention was paid to its overall look of the kitchen because it was regarded as a functional area, not the social space we now consider it. The post-war building of homes saw features such as fitted kitchens became standard and this was one of the areas of the home that arguably saw the greatest benefits of the fully-wired home.

What did the fully-wired kitchen mean for the housewife?

From boiling a kettle, to washing and laundering, or heating and lighting the home, the fully-wired kitchen represented progress and comfort for the family. In particular they represented progress for the housewife.

Most households could afford the cost of basic appliances such as an electric iron or a kettle. They were relatively inexpensive and easy to store.

Larger items such as cookers, which were powered by gas or electricity had replaced the versions fuelled by coal and coke. Basic versions of washing machines, sometimes known as ‘wash boilers’ were gradually replaced by smaller and more efficient versions. Electric washing machines were initially considered a luxury. Towards the end of the 1950s they were increasingly considered a necessity for the modern kitchen. However, they remained a significant financial investment and by the mid-1960s, only 50% of British households owned one.