Anders Myrset: Banknotes from a desperate period

Three banknotes. Three snippets of paper. Three different prints, but with a single purpose: exchanging goods. A form of unofficial currency produced in Weimar Germany in response to the hyperinflation of the 1920s.

A collection of sixty German bank notes, or ‘notgeld’, from that troubled era are held by Middlesex University’s MoDA (Museum of Domestic Design & Architecture). Notgeld or ‘emergency money’ was money produced by German towns, villages, and boroughs from the end of World War I to the mid 1920s. The ‘Reichsbank’, or state bank, struggled to produce coins, as metal was in short supply. The result was the production of temporary currency of small change, usually of paper, and ultimately a collector’s dream – a wide variation of banknotes in different, highly decorative designs. This article looks at three of them.

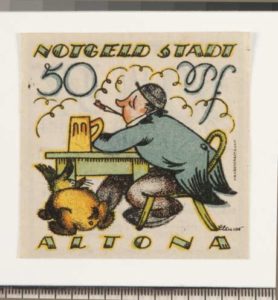

Interestingly, the three notes with the same value – 50 pfennig – are quite different in the eyes of an artist or viewer, making it possible to enjoy the notes, not only as historical pieces, but also as creations of art. Each town designed their own notgeld, and they vary from serious, such as illustrating great historical events, to playful caricatures of society, and illustrations of folk tales. Showing towns’ civic pride, and possibly even how the public viewed themselves.

The first, a notgeld from the town Altona, now part of Hamburg, shows an illustration of a well-dressed man, in a blue coat and black hat. At his feet a dog is patiently sitting, waiting for his master. The man’s elbows are resting at a table, while he is enjoying his cigarette and paying homage to one of Germany’s proudest traditions – the beer stein, or beer mug. The other side is adorned by what seems to be a variant of the town’s coat of arms – symbolising a cosmopolitan city along the river Elbe. The playfulness of the design seems more like a postcard than money, which makes you wonder whether the motif suited its intended purpose.

The second note, from the town of Magdeburg, is more complex, in red and green on a white background. On one side a crowned man on horseback, showing status of authority, with a text translating to: Otto I built Magdeburg, referring to Roman Emperor Otto the Great, who was buried in Magdeburg Cathedral. The man is stretching out his arm, supposedly holding a building with two spires in his hand. Minding the ancient emperor’s affiliation to the city, one might assume that he is holding the Magdeburg Cathedral. The other side shows a gathering of people seemingly waiting for a miracle. A man in a pointy hat is standing on stage in front of a crowd, as a woman is lifting a child towards him. An inscription translates: Once upon a time a doctor Eisenbart lived here and healed people in his own way. Perhaps Eisenbart was a fraudster taking advantage of the crowd’s superstitious beliefs?

Finally, the last note, from the town of Oldenburg, gives the impression of power. On one side a group of people, perhaps a family, is gathered around a bonfire with a boiling kettle. Framing the illustration, is the inscription translating to: Whoever approaches your stove, immediately feels at home here, he considers himself so happy. Even if his travels take him through all the lands, you remain his most beloved land, my Oldenburg! On the other side, roaring lions protect a crest. It is coated in regal colours of gold, red, and blue.

Art from desperate times

Most art can tell much about the period when it was created. Art can take a viewer to a different place, telling stories of lives lived centuries ago. Whereas a painting can show us how people lived and dressed, these intriguing banknotes were part of everyday life. They show images from the period, but more importantly they had an actual function for people. These particular notes – part of MoDA’s notgeld collection – were used in a period that saw the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany.

Life in 1920s Germany was a life in hardship, being forced to live a life in starvation and despair. In the years following the First World War, Germany was thrown into an economic chaos as a result of the debts of war and the harsh settlements in the Treaty of Versailles. Germany was stripped of territory, and as a result seven million Germans were forced to live in areas controlled by other sovereign states.

In the early 1920s the cost of war, and the settlements, were taking their toll, and the Weimar Republic was driven to the brink of collapse. The German currency started to depreciate rapidly against other currencies, and the government issued a flood of new money.

hyperinflation

Because banknotes were printed en masse the value of goods increased by the hour. In January 1923 a loaf of bread would cost 250 marks, whereas in November the same year the price had risen to 200 billion marks. The decreased value of German currency resulted in surreal images of people using trolleys to load money when shopping, collecting wages in suitcases, burning money rather than wood, and children building towers made of money stacks in the streets or using bundles of banknotes to make kites.

The Treaty of Versailles forced Germany into economic disaster and was also a direct factor in triggering World War II. However, though the inflation was a disaster for the nation, there were also winners in the “inflation game”, and many citizens benefited financially from the inflation. This caused friction in relationships between Germans that would persist long after the crisis was over. With the trauma of defeat and unemployment reaching six million, the Nazis gave the nation a scapegoat for the unfavourable economic developments – the Jews. It was then that a charismatic leader of Austrian descent rose to power. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Notgeld today

Today, the desperate times have disappeared into the history books, and the notgeld have found their way into the possession of collectors worldwide, including some to the collections of the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture. The notgeld are symbols of civic pride, and tell us much about the towns in which they were used, and as a result they can be viewed as historical artefacts or as pieces of art. It is up to the viewer to decide how to view the banknotes. The banknotes played a small role when looking at the big picture, but just imagine that these three small pieces of paper were part of the prologue of one of Europe’s darkest chapters. Some art tells stories of lives lived. These three fragments of paper lived their own lives in that period, and that is quite breathtaking.

Anders reflects on the writing process

Writing an article about the notgeld requires a significant amount of reading. I studied history for a year and was particularly interested in the twentieth century, so I had a fairly decent overview of the period and the economic chaos that was caused in 1920s Germany before writing this article.

When I got to pick a piece of design from MoDA’s collection to write about it was an easy choice. However, to write about the hyperinflation and the period itself requires more than just a “fairly decent overview”, and I’ve had to consult different books researching not only the hyperinflation, but also German society in the 1920s. By doing so I hope that I’ve managed to write an article that not only discusses the designs – which are nice – but also puts them into the historical period in which they were made.

I’m happy that my work was chosen to be part of MoDA’s website, as it has given me the opportunity to revise it and receive feedback numerous times. By doing so I believe my writing has improved considerably. This writing process is something I hope to benefit from, as I want to pursue a career in writing when my time as a student is over.