You can also listen on Apple podcasts/iTunes, Spotify, TuneIn, Stitcher and Google Podcasts. Search for ‘That Feels Like Home’ to subscribe, follow, favourite, and share!

MoDA objects relevant to this episode

In the Sunshine of Security

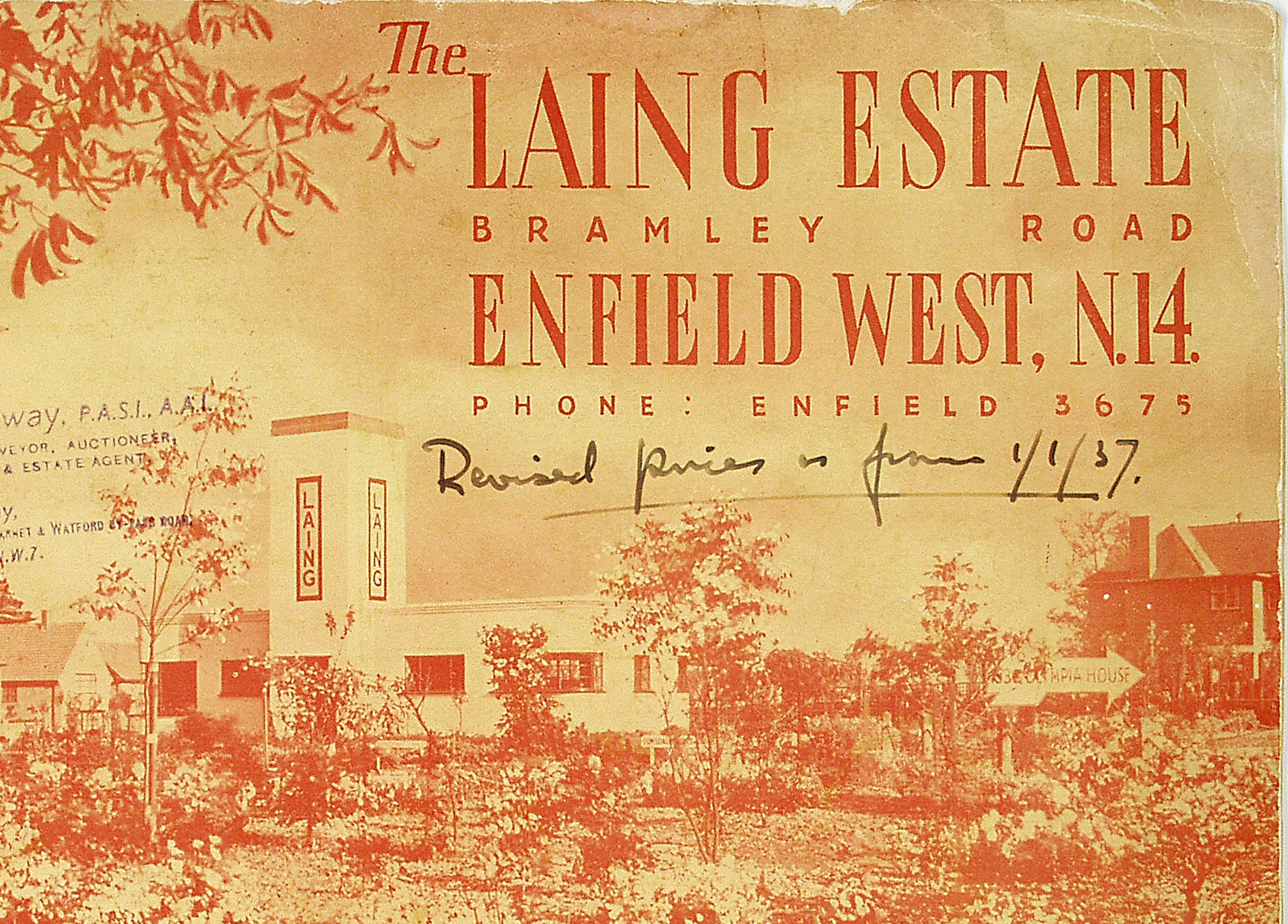

The Laing Estate/ Bramley Road, Enfield, West, N.14/ 3 minutes walk Enfield West tube station|||Brochure for new houses in Oakwood, 1937

Re-Housing Operations

Transcript

Every time we come in, we always here we, my mum, always makes sure that we wash our hands here soon as we’ve been out ’cause here we sometimes have to go to the shops to go and buy our usual groceries and then the important bits that we need. And because of that we’ll end up being in close contact with other people and. Uh, yeah, because of that there is that chance that we could catch it. We always have to wash our hands, and I mean it’s not; it’s almost like you’re not just washing your hands to prevent the virus from you coming to your home. But you’re sort of washing your hands of the outside world..

Ana Baeza Ruiz: Welcome to That Feels Like Home, a podcast by the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture (MoDA), reaching you from Middlesex University in London. I’m Ana Baeza, and I’ll be hosting this second season to explore the multiple stories around home in the current Covid crisis. This time, we’re recording from less favourable conditions, from our homes, so please bear with us if the sound isn’t always of studio quality. And in this season I’ll be talking with historians, anthropologists, activists and practitioners to reflect on the many changes brought about by this pandemic on our homes. As usual we draw inspiration from the museum’s collections to reflect on the present through the lens of the past.

Ana: For centuries cities have brought people and germs together. We only need to look at the histories of medicine and sanitation, urban planning, migration and movement of people, social reform, architecture and activism to see that the histories of health and the built environment are closely intertwined. In this episode we’ll be looking at some of these histories in light of the current pandemic, thinking about how conceptions of disease and epidemiology have evolved, and specifically the role of technology, architecture and design, in prompting new narratives of hygiene and public health.

The conversation will lead us from talking about germ theory, overcrowding and disease in the 19th century to the ideas of modernist architects in the 1930s to reform the built environment. How have pandemics been represented in the past? What are the relationships between public health and socioeconomic structures? To discuss this with us we’ve invited Lukas Engelmann and Elizabeth Darling, welcome Lukas and Elizabeth.

Lukas Engelmann: Thank you great to be here.

Elizabeth Darling: Hello, thank you, great to be here.

Ana: Lukas Engelmann is a historian of medicine and epidemiology. His research covers histories of epidemics such as HIV/AIDS and a third plague pandemic, the history of epidemiological reasoning, as well as the digital transformation of public health in the present. His first book Mapping AIDS from 2018, deals with the medical visualisation of HIV/AIDS. His second book, co-authored with Christos Lynteris is Sulphuric Utopias from 2020 and concerns the technological history of fumigation and the political history of maritime sanitation at the turn of the 20th century.

Elizabeth Darling is Reader in architectural history in the School of History Philosophy and Culture at Oxford Brookes University and her research focuses on modernist architecture in England in the 1920s and 1930s around issues of gender, space and reform. And her book Reforming Britain covers a lot of the issues that we’ll discuss today in the podcast.

Cities and infectious disease

Ana: So it’s a great pleasure to have you here and I’d like to start asking you in the view of the global pandemic that we’re living in, how has the relationship between infectious disease and cities changed?

Lukas: Thank you I think it’s a great question. I think I would firstly say that what has not changed there’s a lot of things that seem to stick to this kind of imaginary association of the space of the city and the emergence of epidemics in the city. And I think going back from a historical point of view it is striking to see that even before the Black Death, before the plague ravaged medieval Europe, you already had this persistent concern in urban environments about matters out of place, about filth, about vapours, about any kinds of stench that needed to be regulated.

But from there onwards up until modernity we have this constant concern about the city as a space in which overcrowding, in which the breakdown of morals, the breakdown of certain social codes and the breakdown of sanitary and environmental cleanliness leads to the emergence of disease, brings disease into stronger and more dangerous forms. But [it’s] also a space in which disease is always imagined to be an uncontrollable and often invisible entity that lurks in the kind of crevices of a city and especially if those are imagined to be very dense.

Elizabeth: Yes I agree with Lukas. I think one of the things that has really struck me about today and the past that I talk about which is in the 20s and 30s but also in the 1890s, are anxieties about the relationships between bodies in space and how you control that and how they are out of control. And particularly issues around the importance of surface and anxieties about what we can see and perhaps even more so what we can’t see; and how those narratives, which perhaps were a little bit in abeyance, have really come to the fore again in the current situation.

Lukas: And I think what is striking is that this imagination of the city as a place from which disease emerged, and often disease is something that is associated with urban life, is something that continues even though theories about disease drastically change. And so when you’re having the Black Death and through much of the late Middle Ages and early modernity a strong belief in disease to be called caused by corrupt vapours or by stenches or what is often called by historians as miasmas, or some kind of gases or smells or just kind of air that is in any way imagined to be corrupted, that is emanating in certain spaces, to be the cause of diseases.

Obviously we can see here the connection between this kind of idea of a putrid air in the dense spaces of cities but the concern about the dense space of the city doesn’t really stop when the idea of disease, and especially the idea of infectious disease becomes much more associated with pathogens and with identifiable microorganisms which still were considered to be lurking everywhere where you can’t see them, which are associated with density, stench and dirt, in many different ways long into the 20th century and up until today.

Ana: I’m interested in what you’re saying about the pathological association with cities, because this also led, as a result, to the implementation of measures to precisely combat disease, measures to the built environment which, I suspect, became more all-encompassing when infectious diseases spread to become epidemics. Can you speak about this?

Lukas: There’s a long list of measures that could be used to fight disease and epidemics and in different times, different places and for different epidemics these measures were very different. Think about smallpox and of course the measure to fight smallpox was vaccination since the early 19th century and the measure to fight a problem like syphilis was certainly different from the measures to fight a disease like cholera which was assumed to be a classic miasmatic disease that were associated with the air before it became associated with water; which then led to sanitation as the kind of key instrument to change the fate of a city with regards to cholera.

However I think we need to take maybe a step back and think about what are these entities that we are dealing with and it’s quite difficult to define this in general terms because of course we have historical views on how these change and we have the views that at the time were also quite pertinent. But I think especially from the 19th century onwards we can think of disease to be this kind of entity that is defined through its appearance in an individual case, an individual sufferer that has a certain kind of disease that is differentiated from other diseases and is treated in certain specific ways. And then the epidemic is really defined as this emergence of many cases of the same disease within a confined space and time.

And of course how we define these confinements of space and time change a lot in different times and at different places. But the epidemic which had been a category of thinking about diseases since classic times, in modernity becomes really this association of what happens when a disease occurs in an aggregated form and if this aggregated form seems to point to some kind of external reason, some kind of origin really from which this accumulated appearance of the same disease at the same place needs to be explained.

So, the emergence of an epidemic brought the place in which it emerges under scrutiny: it brought the kind of people who live in that place under scrutiny and it brought the relationship of the people to the environment under scrutiny at large. And that I really think is the difference coming from the kind of like treatment of individual diseases to the engagement with epidemics in the 19th century. And that is the question of how the epidemic brings society, brings population and brings culture into the frame of suspicion when thinking about pathogenic phenomenon.

Elizabeth: I think in terms of the built environment what happens in major cities in really from the kind of mid-19th century onwards is there’s a kind of tension between do you demolish and rebuild and, you know it’s a kind of weaponry which is assembled to kind of crash through the parts of the city which are identified as the locus of disease and infestation and perhaps a little bit later the source of infectious diseases and the strategy there is a kind of sanitary one. So you kind of have sanitary policies of slum clearance where you identify a problem area, you decant the people, you don’t really worry about where they go and you demolish and you build new tenement housing on a site which is frequently designed on those sanitary lines around a central courtyard. So you have lots of air and light coming in, you have very sheer surfaces, you’re not allowed to put wallpaper up, you have to be vaccinated for example to live in a Peabody dwelling which are built from the 1860s onwards. The doors have gaps top and bottom to get the air through. You have these very kind of apparently very clean kind of environments.

And that’s a very strong tendency from the kind of 1860s right through to the near present I would guess actually, thinking about it, versus much quieter ideas which are about well why not rehabilitate dwellings? Why not make them cleanable and clean? And maybe that’s the way to do things. So two rather different approaches, one which is very visible and shows that you’re doing something as a kind of modern state, another is perhaps the more privately oriented activity that arguably is just as effective.

Lukas: I entirely agree with Elizabeth. I mean especially from the mid-19th century onwards the sanitary movements were an enormously powerful force in many cities around the world and one example that I would pick up here but one could talk about a lot of other examples as well, is Buenos Aires and the sanitary reformer Buenos Aires was called Eduardo Wilde and he was responsible for building all the big green parks in Buenos Aires.

And I think what’s really important about this idea that it’s driven by a quite vague understanding of what makes a city healthy or what makes a city sick in the first place. But these were reforms which were very deeply interlinked with social movements and the social reform that was very much catered to improving the living conditions of the working parts of the city, of the working classes in the city, and engaging with the movements of improving social life also by providing a healthy living condition.

Hygienic modernity

Ana: Yeah and on that point I’d like to throw at you a quote by the anthropologist Mary Douglas from her very famous book Purity and Danger, which links to this idea of hygiene as a sort of reordering of the environment, but I think with all the implications that you were talking about Lukas around social change. And she notes ‘In chasing dirt, in papering, decorating, tidying, we are not governed by anxiety to escape disease but are positively reordering our environment, making it conform to an idea.’ So I’d like you to expand on this notion of hygiene as a kind of ordering as something that’s quite symbolic. How do you see hygiene in terms of how it’s culturally constructed and understood?

Lukas: I often use this concept that has been coined by Ruth Rogaski on hygienic modernity and that this particular period between the late 19th century and into the early 20th century is marked as a period in which hygiene was an idea that far exceeded a kind of notion of engaging with pathogens, or engaging with isolated dangers that were associated with a specific disease that broke out in a specific community. But really hygiene was this umbrella term to associate a lot of different issues under these large-scale campaigns of improving human life or improving the life of humans within a natural environment.

And I think that has many fault lines which go onto many problematic areas, but it’s also this idea of hygienic modernity is really driven by the intent and then also by the plan to create an order that governs nature. And I think in that framework diseases and epidemics were incredibly important, symbolic elements that symbolised the uncontrollable forces of nature. And succeeding in the control over an epidemic would establish a human order over natural forces. And I think this is a really important part of that element at that time, but I’m not sure if Douglas refers to that.

Elizabeth: I think it’s a sort of both/and scenario which is going through my head as I’m listening to Lukas because I think it’s all of those things: it’s that kind of desire to order nature and then when nature fights back through disease and through vermin and bugs and so forth the instinct, the almost atavistic instinct, is to kind of combat it in some way.

But I’m also very mindful of how in your 19th century overcrowded tenement in the Old Town in Edinburgh you were constantly surrounded by the consequences of living in overcrowded, insanitary accommodation and you didn’t have access to a loo, you didn’t have access to running water and yet you had eight children to care for and to bring up and you were probably malnourished as a consequence. So there’s a kind of tension I think between the realities of living in an environment where it’s just not clean and you don’t have penicillin, you don’t have antibiotics, you don’t have any of the weaponry which we take for granted today and the things you’re living with are both visible in terms of dirt and vermin and invisible, these diseases which your children will catch and you can’t do anything about, they’ll die of measles.

So there’s a kind of risk of pathologising or demonising a genuine kind of concern to make conditions better, as Lukas was talking about, earlier; but there’s also the sort of slippage between when that becomes sort of super-fetishized. So sanitary slum clearance is great on one level, some people get better housing, but one of the consequences, and this is what happens in Edinburgh in the 1860s and 70s, is you knock lots of insanitary housing down but you don’t rehouse everybody because you can’t, so everybody just moves further south down in the old town into even more overcrowded dwellings.

Lukas: Yeah if I could just add I think there’s also this paradoxical element in that history that Elizabeth’s just touched on very nicely and I think that’s like if you think about the fight against epidemics as this kind of control over nature we often forget that there’s also this long-standing tradition of thinking about epidemics as diseases of civilisation that also was very present at the 19th century. So to think of epidemics as something that has emerged because of human cultural advancements, as they were classed at the time, because of the urban living, because of the kind of lifestyle that were adopted and there’s a thesis in German which speaks of civilisation at syphilisation [sic] so with syphilis instead of civil, as this kind of like where there is civilisation there will be some kind of epidemic disease because it is an outcome of culture rather than an outcome of the nature that is inhabited. And I think one really has to think about these like questions of where do diseases come and how is disease deposited within this dichotomy of nature and culture to then think about the question of dirt and how we navigate our anxiety to that in the words of Mary Douglas.

Ana: Yes, and on this idea of civilisation, in inverted commas, I guess one prime example in Europe is the modernist project of urban reform as a reform of the social body. Elizabeth, you’ve focused on 1930s projects by modernist architects in Britain – can you flesh out some of the ideas within that project (if we can call it so)?

Elizabeth: I think what’s really important to understand about what happens in 1920s and particularly 1930s when things tend to get built rather than being the ideas they are in the 20s, is a kind of coming together of a whole range of reformers, all of whom have a kind of broader project of envisaging a particular type of modern, very often it’s actually a modern England, which becomes a kind of cypher for the nation and the Empire and which is about a particularly sort of civilised, self-responsible, white, working class who play their role in what is becoming a full democracy and understanding their role within it and taking their place alongside their middle class and upper class co-citizens.

And you have the people who are interested in the kind of purely social aspects of that, which might be to do with health or education, citizenship more generally. And then you have the idea of how that might manifest spatially what you do in terms of the built environment to create settings in which that form of modern Britishness, Englishness, can be performed. And I think ideas around putting people into a position where they can be healthy first of all, how you can mend the family, which has been jeopardised by living in overcrowded slum conditions, so how you can create an environment which in many respects is the kind of antithesis of the slums, so it’s not spatially disordered, it’s not overcrowded, it has amenity, it’s visibly different and it’s visibly clean.

So projects as varied as Kent House which is this modernist block in Chalk Farm, commissioned by St Pancras House Improvement Society, from Connell, Ward and Lucas, one of the leading modernist practices in the day, or Kensal House in Ladbroke Grove in West London which is completed in 1936; these are environments where if you look at the plan of the flats everything has a place. You’ve got enough bedrooms to separate boys from girls and from their parents. You’ve got a large living space. You have a modern kitchen often with state of the art mid-1930s equipment, and you have a bathroom… and you have a separate bathroom and loo. You have hot and cold running water. You have all the things which you don’t have in the slum so that you can have a proper family life so you can fulfil your role as modern, reproductive citizens and you can also be a citizen consumer by buying nice things which will go in your flat because you’re not forking out a fortune as you would be in slum accommodation.

And I think if you look at some of the social reform rhetoric, and I’m thinking particularly of some of the housing films which were made in the late 1920s and the 1930s, like Housing Problems which is made in 1935, for example, which is a very powerful film not least because it has slum tenants talking to camera about their experience. And one of the people who’s filmed is a guy called Mr Berner who is a sort of young working class man who’s dressed up in his kind of Sunday best talking to camera and one of the things he says is very powerful, he looks to the camera and he says, ‘A lot of people don’t understand what it means to live in one room,’ and he’s there with his wife and they’ve got two children. And he says, ‘I’m really excited about the fact that we’re getting new flats,’ and he says, I’m looking forward to the day,’ and I quote, ‘When every working class man will have a hygienic flat to live in, where cooking conditions is better, living accommodation is better, sleeping accommodation is better, and what’s more we have a bath.’ So I think you have there that sense of what an ordinary working person wants because they can’t get it when they’re in the slum and they understand that that is the basis to, you know, kind of basic human rights of accommodation and you can’t do anything if you don’t have that.

Sanitising practices

You’re listening to That Feels Like Home. I’m Ana Baeza and in this episode I’m talking to Lukas Engelmann and Elizabeth Darling about histories of health and the built environment. We’ve been talking about urban spaces, infectious disease and hygienic modernity, and now we’re going to move onto discuss how sanitation evolved as part of the modernising efforts…

Ana: So we’ve been talking about modernity and debates on hygiene and health quite broadly, so I’d like to drill down on these a bit more. And particularly your work, Lukas, has addressed very concrete sanitation practices in the USA that develop in the turn of the century as part of this hygienic modernity. What was that all about?

Lukas: It’s striking to me how many parallels there are between this development of the hygienic living space and the development of the hygienic city but also of a hygienic world really. And this is one of the issues that we were working with on our research on fumigation but we focused mostly on fumigation in maritime trade, because what we were really interested in is this very longstanding debate that went through the 19th century that looked at quarantine as a huge obstacle to trade and especially to trade within the empires and the colonial fabrics.

And so the issue was always that where you have quarantine in place to protect the city from the arrival of any kind of disease, you would have a number of days in which ships were not allowed to enter a port. And it had to wait, sometimes up to 40 days as the word, it emerges from old Latin, kind 40 days of quarantine or sometimes even 60 days, sometimes 100 days depending on the different year and place. And this was of course seen to be a huge problem for successful trade relations and for successful import of goods from overseas and mostly into the West. And that relates then to what has been quite a staple in the history of medicine and in the 19th century this conflict between what is often called contagionists and anti-contagionists and there was two groups really who were arguing in many different places across Europe, as also in the US, if such a thing as an infectious disease really exists or if diseases are always to some kind and sometimes even predominantly caused by pre-existing factors that are able to be found in the environment or into the human host.

So the question was, is an epidemic caused either by something that can be identified as a pathogen that circulates, that travels and that enters into the human body and that multiplies and then enters into many human bodies to cause an epidemic? or is a disease something that may or may not relate to a microorganism but it only emerges as an epidemic if the constitution of a certain population is too weak or if the environment in which this population lives, for example the urban environment, predisposes the population living there to the disease? Of course you can see how that interrelates with racial and with class tropes that were folded onto this.

When it comes to quarantine of course quarantine did only make sense if you have a concept of a pathogen that is somehow travelling either within the bodies that are travelling or within the goods that are travelling. If you would side with the theory that argues that a disease emerges in an epidemic form because of conditions that are strictly local then quarantine wouldn’t make any sense. And of course that kind of theory was the theory that people who were interested in keeping trade successfully running would more likely associate themselves. So there was always this opposition between those who were imposing strict regiments, and those who were in favour of a functioning and profitable economy and I think that’s one of the tropes that we can see travelling all the way through to today.

In late 19th century and specifically after the civil war in the United States the idea of contagion becomes much more solidified and consensual. And this is where one of the heads of the board of health in Louisiana begins to think about a different method to…to organise quarantine and to go away from what he called this barbaric practice of just isolating ships, the trade, goods and people for 40 days or longer but to think of a method where we can use scientifically proven agents, gases it was mostly thinking about, to destroy all the pathogens and everything that these pathogens could travel in. And he developed a system that was built around sulphuric acid gas, there’s a whole story why sulphur became incredibly cheap at that time, and sulphur was also something that was a very highly traded good, especially in Louisiana, so there are many things coming together at that time here in the 1880s. But he then developed a kind of machine that he installed at the former quarantine station down the river of the Mississippi from New Orleans in which the ship would land and everybody, all the passengers would disembark and the ship would then be pumped full of sulphuric acid gas with the assumption that every pathogen, every vermin, every insect, and even all rats and mice who might be living on the ship would be exterminated immediately and the ship could unload whatever it had in valuable trade the next day downtown in New Orleans.

Ana: I think it’s really fascinating just to hear you speak about these techno-scientific and economic arguments that are made but also how this kind of material intervention into the environment and I wonder how that translates into similar debates in architectures of health that may have also been dealing with contagion which is something Elizabeth that you’ve been looking at, especially in relation to the Finsbury Health Centre where, as I understand, there was also an efficient segregation of different spaces within that environment and how that links to the kind of things that Lukas was talking about.

Elizabeth: I think it links in, in several ways. So Finsbury Health Centre is part of what was called the Finsbury Plan, so this north London borough which is I think it’s the most overcrowded and has one of the worst mortality rates in London in the 1920s and 1930s. And in 1934 it gets a new Labour council which is determined to show what a socialist political strategy can do to improve the lives of the working classes, and it develops a kind of multipronged attack, a fundamental basis of which is a kind of renewed public health policy.

So there is going to be slum clearance, there’s going to be a new park, there’s also air raid precautions because they’re becoming aware of probably an impending war and core to that and the thing which is built first of all is a new health centre. And the idea is to bring together, so to kind of agglomerate all the public health facilities for the borough in a kind of state of the art building. So you have the public health director of Finsbury who’s an expert, working with a team of expert architects who he’s seen exhibit their work, their design for a TB clinic in East Ham, this is a practice called Tecton who are developing the idea that architects gain their expertise through research and the assimilation of that research into new forms of architecture. So you have a coming together of a kind of technocratic vision of the future and the idea that you can have harnessing technology to improve the world for everybody but particularly in this context the working classes.

And Finsbury Health Centre which brings together things like dentistry – there’s a TB clinic, there’s ultraviolet treatment for children with TB and rickets, so you have this building which on the one hand has a kind of ground floor with a large open foyer where people can gather. The clinics all are at ground floor level so they’re easily accessible all in their individual separate space. But round the back you have a separate entrance and there’s a fumigation station where the belongings of people who are going to be moving into new accommodation can be fumigated, and I think also people themselves can be fumigated. And they’re kept very separate from, if you like, the transformative parts of the building which are round the front and accessed along a rather grand processional ramp which goes into the building. So this very striking building which, you know, is clad in gleaming ceramic-y tiles, a sort of slightly off white hue, this low rise building in a very densely packed urban environment is this very visible symbol of the transformative possibilities of proactive healthcare and it eradicates disease in the past in the same way as that kind of fumigation station will eradicate all the bugs and beasts that lurk in people’s belongings.

Representing epidemics

Ana: And I think there was something that struck me there in what you said Elizabeth about this image of health and I think you used the expression in the past about the Finsbury Health Centre being a megaphone for health. So there’s this question also of kind of publicising these ideas, of making them visually accessible, so I’d like to move on to discuss some of the visualising strategies, both around health and hygiene campaigns but also around visualising epidemics, so I don’t know who would like to start but I think that’s quite a rich subject that I’d like to just take some time to consider.

Lukas: I would actually start with the third plague pandemic because the project I was working on which was led by Christos Lynteris was built on the assumption that the third plague pandemic was the first pandemic that was photographed so it emerged at a time when not only bacteriology and a lot of scientific approaches to disease became more pronounced in the late 19th century into the early 20th century, but it also emerged at a time when photography became popularised to a huge extent.

And so if there’s anything to be said, that was the assumption, about how an epidemic photography might look like and how it might be different from what we know about, let’s say, photography in the laboratory, micrography or photography of diseases in medical photography, if there is anything that is uniquely distinct about epidemic photography then we should find it in this global archive of photographs related to the third plague pandemic. And one huge surprise that we had was the assumptions of what we would find were entirely wrong. I was expecting to find archives which would have series upon series of pictures of buboes. I mean the bubo was an iconic symptom of an evenly iconic epidemic, especially with the Black Death has a huge historical aura, that is constantly being re-invoked and being talked about even today in reference to COVID-19 as the kind of like standard example epidemic from which we supposedly can learn everything.

But instead what we found were predominantly pictures of streets, of houses, of environments, a lot of photographs concerned with measures, with cleaning measures, with kind of building up quarantine zones or building internment camps that were erected: measures of cleaning or even sometimes pictures of burials; pictures of kind of the hygienic state of the burials; pictures that were trying to frame this pandemic as a pandemic that was on the one hand under control and on the other hand it was a constant visual investigation of what was actually bringing this pandemic, what has actually brought this pandemic to the fore in the first place. And I think you can always imagine, often imagine looking at these pictures it was this kind of constant question of as to why is this disease coming back now when modernity has achieved so much of different form of lifestyles around the world why is this menace of medieval times returning? And photography was there to kind of like frame this question, kind of open-ended by looking at the environments in which the disease emerged.

Elizabeth: I think I would come at it from a sort of parallel, complementary perspective and I’m thinking about how important photography is in raising awareness of conditions which might create disease or create difficulties in living generally and how integral that is to reformist projects from the later 19th century onwards. And I think I’m also interested in the kind of nature of data gathering and how important information which is maybe part of trying to control these problems, it’s a very proactive, it’s something you can do, you can gather information, you can gather data about mortality, you can go and investigate.

And then depending on who your audience is, who you’re trying to persuade to do something about this I think visuals start to play a more or less important example. So whereas a statistician or a medical officer of health might be very comfortable with a column of population data if you’re trying to persuade a potential donor to your reformist charity, for example if you’re interested in building housing in Edinburgh in the late 19th century, for example, or whatever then you have to take a different tactic and photography and visualisation, that might be graphs.

I’m thinking of Florence Nightingale a bit earlier and her pie charts, you know that becomes very important; and I’m thinking of things like, you know Dr Barnardo and his photographs of children before and after they come into his homes, a lot of attention played to children, photography of children in these contexts. I’m thinking of Jacob Rice whose photographs in early 20th century New York and the importance of showing the human cost as it would have been characterised I think of living in environments. And also making people aware that these places exist because a lot of times people just don’t go there, so it’s very easy to not know.

And one of the reasons produced photographs and later film is particularly housing associations in London in the 20s and 30s they use films in people’s drawing rooms when they go round to raise funds. So they’re showing a film of someone making a coffin for a dead child in an affluent living room in North London. There’s a very powerful message being relayed there of showing a child who’s died because of where she lives in a very richly appointed drawing room. So the kind of tropes which are used become fairly repeated but the aim is the same it’s to sort of raise awareness, to raise consciousness and out of that action.

Lukas: If I just could briefly add I think this is a sort of really interesting, coming back to fumigation through that because one thing that happens, is that in some places the fumigation practices that have been developed for maritime trade and to really kind of cleanse out ships do land in urban spaces and are being taken up in some urban spaces, especially in Latin America, especially in Buenos Aires and in Rio de Janeiro where you then have these massive fumigation campaigns that go through the city systematically and cleanse out every single house and cellar and every single building to provide the kind of like a cleansed city as a mode of prevention to the expected arrival of plague.

And what’s most important about these measures is that they’re always being photographed and circulated in the newspapers as this kind of demonstration of the active state preventing the disease from arriving, being proactive and creating a hygienic environment that is safe to live in and in which this safety is guaranteed through the spectacle of fumigation, through cleansing the air. And I think there photography again visualises the epidemic through the measures that are being taken up against the epidemic to create the framework of control against the risk or against the crisis or against the coming crisis or the coming plague.

Elizabeth; Yeah I’m certainly thinking, you know the kind of importance of contrast and before and after. So in slum clearance films you know they all follow a standard narrative of panning over the rooftops of slums, going into a slum showing its horribleness etc. maybe some interaction with people who live in slums and then the after story of being rehoused in your wonderful flat.

And it’s just as you were talking about that Lukas I was thinking of the, what’s now becoming a kind of common thing on the evening news now which is watching people who’ve had COVID-19 and they recover and then we see them coming out of hospital, walking or in a wheelchair and being applauded by the hospital staff. And it’s that kind transformative narrative which is so important in showing that things are being done and showing that things have been done. And that’s really underpinning a lot of what we’ve been talking about I think in terms of visual representations.

Ana: OK, so images have had a performative function, as part of campaigns around statehood, public education, etc…but do we know much about how these images were circulated, who they reached, and how they were received at their time?

Lukas: I think for the case of plague we know that these pictures were, I mean some pictures were printed in reports and these were then circulated among epidemiologists. There were plague conferences which were discussing the progress in measures against plague and to contain plague, which were often proceeded by the production of voluminous reports that would just put everything together that was considered to be important and interesting about those and they were often like appendices with lots and lots of photographs in there. But many of these photographs also just disappeared in the archives, many of them were unearthed only now when we kind of like discovered them and put them into an open access available archive.

But I can switch to a different case and talk a little bit about photographs in HIV and AIDS where I think this is a much more political and a much more problematic issue, or it has been a much more problematic issue and where what was beginning in the early days of AIDS in the 1980s as a kind of clinical practice of capturing the wide range of devastating symptoms that were associated with the outbreak of AIDS in an individual patient these photographs became very quickly embroiled in a kind of media representation of the people who are at risk of AIDS and therefore were used to frame a risk group and were used to frame gay men as the kind of group that was effected by this epidemic, the group that was somewhat responsible for this epidemic and were suffering from what has been called often a deserving illness.

And so these kind of like frames of the person with AIDS as being suffering from symptoms that are somehow the result of the lifestyle they’re living, and they were all embroiled into the visual politics of how do you actually represent the person with AIDS and what is it that you want to show there? What do you do when you show the person with AIDS to be isolated, suffering from devastating symptoms and dying left alone, while ignoring that there is an enormous amount of community efforts, community care, but also that there is a disease that effects so much more than just this isolated risk group and so on and so on. So here in the case of AIDS in the 1980s for clinicians probably were very surprised about that very inconspicuous genre, clinical photography capturing the symptoms on people with AIDS became embroiled in these like politics of what as a society do we want to actually think about when we consider the person with AIDS and what responsibility do the media, but also does medicine have in framing and guiding those representations?

Elizabeth: What I was thinking, I mean to take us back pre-AIDS back to my period and sort of work that I’ve been doing what’s very clear to me about what people think they’re doing when they’re doing their housing exhibitions or they’re making housing films and they’re creating information about what they’re doing this rests on the basis that if people have information they will act. And I’m thinking of another health centre project, the Pioneer Health Centre, which is in South London and starts in 1924 and runs through the interwar period in various manifestations and they use a lot of disease analogies in their work and they talk about people being infected with good example and that they will behave differently if they’re exposed, you know another kind of interesting disease-y kind of metaphor, to good example, to opportunity. And there seems to be that kind of metaphorical way of thinking which underpins a lot of the reformist activity that I’ve looked at in my research is that you can kind of infect people with right thinking and if they’re susceptible to it, which in various contexts might have a eugenic kind of overload to it, they will respond and act properly, and again this constructed idea of what that might be, and agitate for change.

And whether the effectiveness of that is on one level quite difficult to gauge but certainly, you know my housing associations in their campaign work they get money and they are able to build and to effect change that way. So something’s working, whether it’s the visual culture I don’t know, whether people are shocked by what they see it’s very difficult to gauge and unfortunately it would be great if you had that kind of evidence in the archive but I’ve yet to find it.

Ana: Yes so I think both of what you’re saying brings to the fore what the different purposes and aims that have accompanied this sort of visual culture produced around epidemics, moving forward into the present and thinking about COVID I know Lukas you’ve specifically written about the representation of COVID at the moment, we’re not just talking about photography here, right, we’re talking about a whole series of newsfeed updates, different interpretations, social media, and I think Lukas you’ve mentioned something about this offering a simulation of sorts of the pandemic.

Lukas: Yes that’s something I’m thinking a lot about at the moment and thinking about COVID-19 and I think we’ve seen a lot of historians weigh in and bring in comparison to the 1918 flu or the comparison to the Black Death as I mentioned before, or comparison to pandemics at large; on the one hand we can see there is a lot of analogies and thinking through the work I’ve done on photography and on maps and other things and we can see all of these registers being used again, COVID-19 is that we can see beautiful models of the virus and how it’s kind of explained and its functionality and its effects. We can see maps of the world. We can see where the virus is and how it distributes across the world and we can see of course a lot of photographs of the kind of places that are infected or the people or, as you mentioned, the people who are the convalescent, the recovered people who are leaving the hospital triumphant over the disease and all these tropes are being activated.

But one thing that struck me that is from what I can see really different about this pandemic at this time, to all of the pandemics that I know of in the past is really the speed in which we are being informed and are being in the present of this global crisis, or even being made to partake in this global crisis. I got curious about a term that many epidemiologists use today and that’s the term that’s called ‘nowcasting’ which is a term which has been used in meteorology and in economics and it’s a way of trying to use data scattered often every little data from the recent past, the data that you have and you use some assumptions about the development of large scale phenomena and you model out of that data a likely scenario so that you can, quote/unquote, predict the present.

And that’s something that I thought was striking when we look at the way that we are being informed about the pandemic, the way that we are consuming the information about the pandemic. Think of the dashboards that Johns Hopkins University provides or think about the daily updates where we get data on mortality or data on case rates, on testing. And although we all have learnt now that these data points are never fixed and are often subject to historical change once data has been rearranged, one’s kind of like values have been corrected, once the national statistics office has weighed in and so on, we are still accepting these kind of like daily snapshots as the kind of daily state of what the epidemic is.

And I’m not quite sure where I’m going with this in my research and how to think about this but it struck me that this is something that we have not seen in the epidemics in the past, that we have not seen, not even in the case of AIDS as a kind of assumption of permanent update of the pandemic. And I wonder what the effects of these are and in particular as we are confronted with updates, with these snapshots as something that, for lack of a better word, we have to understand to be simulations, there are possible scenarios that are being presented as the actual state but then from hindsight we often see that these states are changing and that these states are not as fixed as we assume that they are.

Elizabeth: Yeah that’s so interesting because it’s yeah we’re in a continual state of being informed but in a way maybe we don’t have a benchmark, a starting point for assessing that in some way because we’ve got so used to not having…because we’ve controlled disease so effectively more or less we haven’t had to think about it. And as you were talking I was thinking about the almost, I’m going to say, atavistic for want of a better word but you know the kind of things to which we’ve retreated in order to be able to cope with this thing, you know. And how oddly that’s very reminiscent of what people have done in the past which is become obsessed with hygiene, become obsessed with ordering; and the kind of immediate thing that everybody did when this started was buy lots of cleaning material because you know if you can clean it, you can’t see it but if you can kind of spray stuff everywhere well hopefully that might help, you know that we are obsessively washing our hands and using cleansing gel.

And kind of the mask has become a kind of sign of how we’re dealing with this, do we wear a mask, do we not wear a mask, maybe you know all those kind of things seem to be things to which we cling because they’re signs of being able to manage something invisible and enormous. And part of which is that huge slew of constant information, so you kind of almost retreat to what’s worked before even if we’re actually maybe doubtful whether it does but it makes us…it’s a way to control things which I guess is one of the things we’ve been talking about today.

Lukas: I think it also led me to reflect a bit on the role of historians with regards to pandemics and there is a certain aspect of the way we look at pandemics that we…we are very, we’re deeply connected to the kind of narratives that we associate with the pandemic and I think the narrative of this pandemic is not yet told and it can’t really be told unless you are in hindsight. At least that was an assumption that many used to have when approaching epidemic and pandemic phenomena but now we see a situation I think and just touched on that where we see this inflation of narratives constantly going on and constantly being retold and constantly being reshaped and reflected. I mean the story of the…the toilet paper crisis is already so long ago and has been overshadowed by so many…over-layered by so many other stories that are already associated with COVID-19. I’m very cautious to give them any kind of resolute framing because I think this is so in flux at the moment that I’m not quite sure what will stick.

Lukas: I think the history of epidemics is a rich reservoir to…to look at the history of racism because almost every pandemic, almost every epidemic event had some form of us and them built into the understanding of it. In the case of AIDS and HIV it’s through the framework of the risk group and in the case of the plague, or in the case of other older epidemics it’s much more blatant through the assumptions of a western superiority that is either understood through the achievements, quote/unquote, of modernity or through the assumption of some kind of racial superiority that is ingrained.

I think looking at COVID-19 it’s this old trope is coming out that we…that…that I think has been used a lot in reflections on COVID-19 is that an epidemic makes persisting structural problems of society visible and it makes them visible in an almost too – not too but it makes them visible in very bright and very clear contours and I think there we see that we have a residue of structural deficits and a residue of structural inequalities that are exacerbated by a lot of silent and invisible practices, institutions, infrastructures and so on and all of those come now under scrutiny by searching for the cause of these inequalities that are so clearly marked in the data coming through on COVID-19.

But my word of caution with regards to comparisons with the history was while we have this motive of othering in almost every epidemic and the idea of a deserving illness that is followed on various populations, it’s very important to pay attention to the detail and to really look how this is explained in different epidemics and how it’s associated with different categories of othering. And so I think it’s a very different kind of problematic practice if you associate an epidemic with a certain population because of their lifestyle, because of their cultural practices, than if you associate an epidemic or a disease with certain people through assumptions about their genetic inferiority, which might be the result of, or which might be imagined as a result of their…their…their population over generations. Or if you look at an epidemic through the lens of kind of the question of where people live and how the environment impacts on that, even that is not innocent and has not kind of like…cannot free itself from assumptions about the kind of populations that live in there and what they live through. So my point here would be really to look carefully at what kind of othering happens in history and how we might learn from those different kinds to be very attentive to the risks of making quick assumptions and to make quick explanations in the case of COVID-19 today.

Elizabeth: I think Lukas has put that very well and I think one of the things which this has thrown up is, you know it makes us have to think about lots of very uncomfortable things which again we normally don’t want to have to think about which are these structural inequalities in our world and you know the human impact of that and again that’s going to take a long time to kind of process and to kind of be able to measure I think in any form like historical, contextual way.

Health Futures

Ana: Yes, this has thrown up lots of things, but also possibilities for intervening at the level of discourse, policy, so I wanted to finish by asking you what do you hope for the future of public health?

Elizabeth: When I was thinking about that question because you gave us some pointers and I wrote down, sensitivity about space, and that one of the things which for me has been a real reminder as a woman who occupies, tries to occupy space, this is something which I think we all know but I think one of the things the pandemic has thrown up is…is how…is a reminder of how space, who has space, who doesn’t, who feels they have the right to occupy space blithely and unaware…unawarely, if that’s a word.

And one of the things I think this has shown very plainly is…is that there are a lot of assumptions underpinning who goes where and who has the right to go where and my hope might be that we…we non…people who are affected by these things, might become more aware of the way they use space and that their assumption of a rightness to invade my two metres, or whatever, and that maybe out of that there might become a more equitable sharing and ownership of space because I think it’s been brought home very clearly watching people in space. And that has public health implications and it might be interesting to see how that could become part of a kind of broader rethinking of how our…the spaces that we occupy are used. So that’s kind of what I might…one of the things that I’d hope might come out of all of this.

Lukas: I think I’ve two or three quick points that I would raise. One is I think we need to be more imaginative about the kind of language that we use when we define the relation of humankind to epidemic and pandemic threats and I think we would do best to get away from the kind of tired reiteration of military language and war metaphors to…to…to situation us as humans in this framework in which we depend on that is the environment in which we live and which brings out threats for all kinds of reasons that are in very complicated ways entangled with our life and our lifestyles and our…our place of inhabitation.

And so I think the second point would be beyond this language is to really think about like the ecological frameworks in which we live and to assume that a future of…or moving into the future that we need to think more broadly about the…the…I guess the question of cause and then the question of what makes pandemics and epidemics to emerge in the first place and to not fall prey to simplistic, deterministic models where there is just like one random incident in a wet market somewhere and from there a global pandemic comes but that there is a chain of elements and conditions that we are very much responsible for and in control of, global trade, a globalised economy, a form of kind of like society that is deeply structured by inequality, especially on a global scale and so on, which all take part in that. So it would be a plea for more…for maintaining complexity when thinking about the cause of epidemics and pandemics and really looking at that complexity which can be very challenging because it makes it almost impossible to find any kind of clear, identifiable cause on which we can act on but we always need to have a more broader and a more systematic view on this.

And I guess as a final point I am really sometimes looking at public health messaging and public health representations, I think we need to be more open with the fact that we cannot build an assumption in our public health messaging that everyone will act rationally on the basis of scientific knowledge if it’s just kind of like put out there but that we need to be also…have a better way of engaging with public health messaging so that we can acknowledge the kind of residue, and that goes back a bit to Mary Douglas of kind of like the elements of control but also the elements of the abject and of the uncanny that populate our life and that they very often also make our lives very enjoyable and which also very often are very elemental part of the kind of social life that we all live and that we kind of like need to find balances where this also can have a place and where hygiene does not become the dominant framework to define how we enact with each other.

Ana: Great. Well, thank you very much Elizabeth and Lukas for joining us in this conversation. I personally feel I’ve learnt a lot today I’m sure our listeners have as well so thank you.

Elizabeth: Thank you.

Lukas: Thank you I have also learnt a lot.

Elizabeth: Me too.

Ana: A huge thanks to Lukas Engelmann from Edinburgh University and Elizabeth Darling from Oxford Brookes, for taking us through some key moments in the urban histories of epidemics, health and sanitation. In this episode you also heard the voice of Matthew Patenall, who contributed his experiences of home washing and hygiene during lockdown, thanks so much Matthew. I’m Ana Baeza and this podcast is brought to you by the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, Middlesex University. We’ll be back again with episodes, touching yet more aspects of home life and the everyday under Covid. Stay tuned.

Further Reading

Curtis, V.A., 2007. A natural history of hygiene. Canadian Journal of infectious diseases and medical microbiology, 18.

Curtis, V.A., 2007. Dirt, disgust and disease: a natural history of hygiene. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 61(8), pp.660-664.

Darling, E., 2017. Womanliness in the slums: a free kindergarten in early twentieth‐century Edinburgh. Gender & History, 29(2), pp.359-386.

Darling, E., 2014. From cockpit to domestic interior: the Great War and the architecture of Wells Coates. The Journal of Architecture, 19(6), pp.903-922.

Darling, E., 2007. Re-forming Britain: Narratives of modernity before reconstruction. Routledge.

Darling, E. 2002. ‘To induce humanitarian sentiments in prurient Londoners’: the propaganda activities of London’s voluntary housing associations in the inter-war period.’ The London Journal, 27:1 (2002), pp.42-62

Darling, E., 2000. ‘Enriching and enlarging the whole sphere of human activities’: The work of the voluntary sector in housing reform in inter-war Britain. In Regenerating England (pp. 149-178). Brill Rodopi.

Dion, D., Sabri, O. and Guillard, V., 2014. Home sweet messy home: Managing symbolic pollution. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(3), pp.565-589.

Engelmann, L. and Lynteris, C., 2020. Sulphuric Utopias: A History of Maritime Fumigation. MIT Press.

Engelmann, L., 2019. Configurations of Plague: Spatial Diagrams in Early Epidemiology. Social Analysis, 63(4), pp.89-109.

Engelmann, L. 2018. Mapping AIDS: Visual Histories of an Enduring Epidemic. Cambridge University Press.

Engelmann, L., Henderson, J. and Lynteris, C. eds., 2018. Plague and the City. Routledge.

Engelmann, L., 2016. Photographing AIDS: On capturing a disease in pictures of people with AIDS. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 90(2), pp.250-278.

Kehr, J. and Engelmann, L., 2015. Double Trouble. Towards an Epistemology of Co-infection. Medicine, Anthropology, Theory, 2(1), pp.1-31.

Olivarius, K., 2019. Immunity, capital, and power in Antebellum New Orleans. The American Historical Review, 124(2), pp.425-455.

Useful Links:

Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic. Open Access Image Repository: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/275905

www.c20society.org.uk/botm/sassoon-house-london/

http://somatosphere.net/forumpost/covid19-spectacle-surveillance/

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1078340

Show Notes

Credits

Produced by Ana Baeza Ruiz, with guests Lukas Engelmann and Elizabeth Darling

Editing by Ana Baeza, Zoë Hendon and Paul Ford Sound

Contributions from Matthew Pattenall

Music Credits

Say It Again, I’m Listening by Daniel Birch is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial License

Let that Sink In by Lee Rosevere is licensed under Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0)

Would You Change the World by Min-Y-Llan is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License.

Phase 5 by Xylo-Ziko is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License.