Many familiar domestic objects within Britain’s homes are intimately linked to imperial histories and geographies. In this episode we take MoDA’s collections as a starting point for discussion around the sale and home display of embroideries from China, of exotic goods in department stores like Liberty’s and the impact of Empire on suburban life. We also discuss how homemaking has connected the idea of the household to ideas about the nation and empire.

You can also listen on Apple podcasts/iTunes, Spotify, TuneIn, Stitcher and Google Podcasts. Search for ‘That Feels Like Home’ to subscribe, follow, favourite, and share!

MoDA objects relevant to this episode

Yule-tide gifts

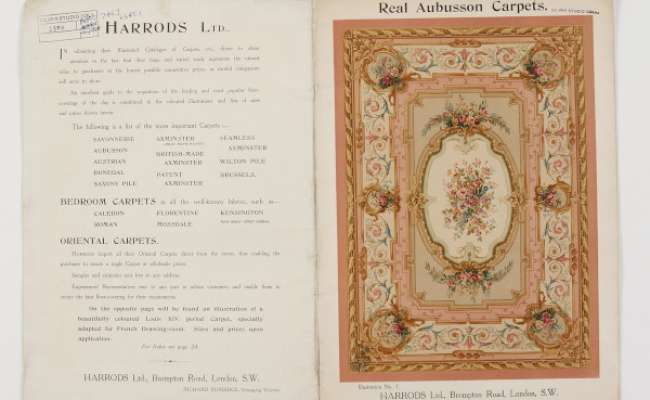

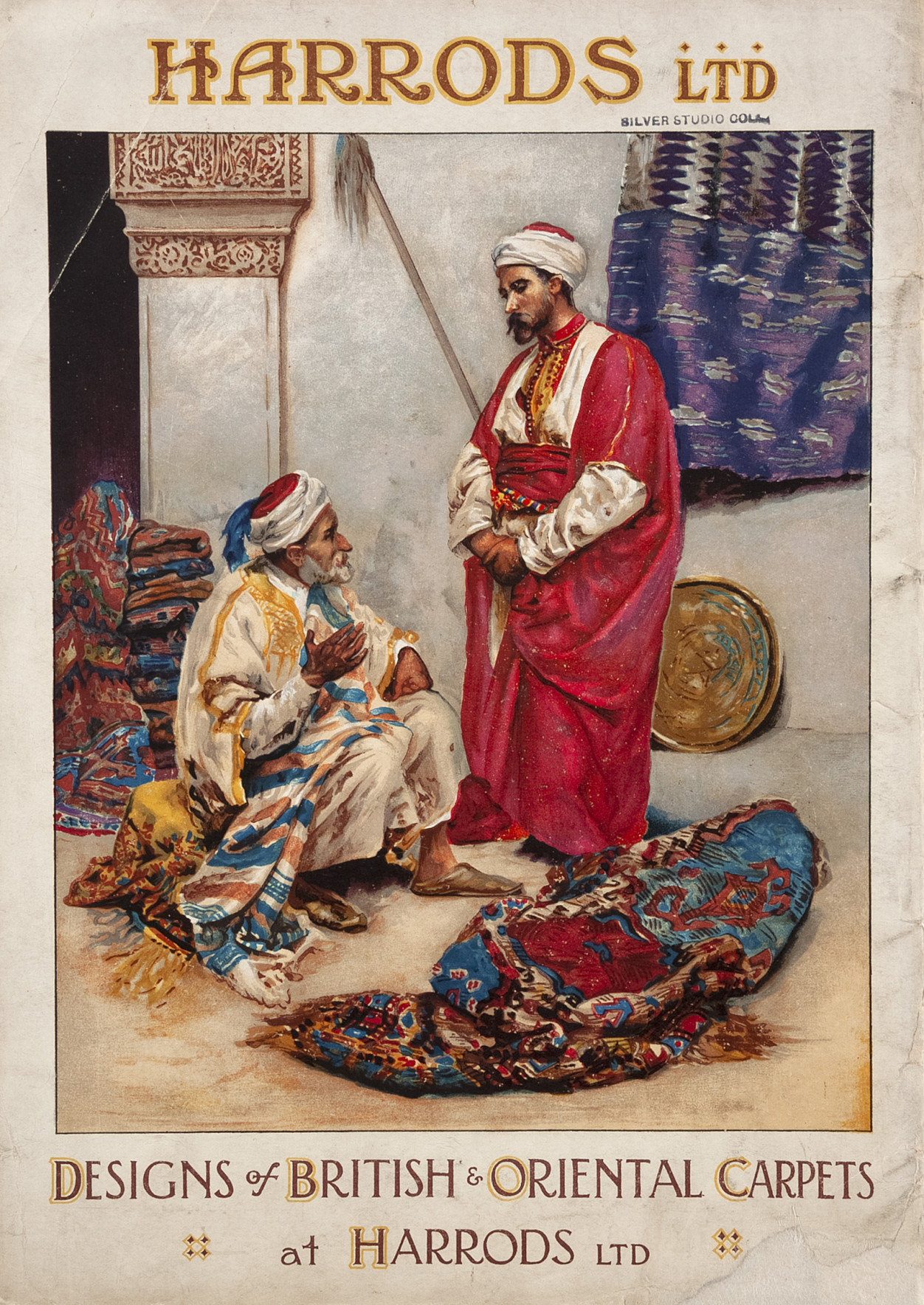

Designs of British and Oriental carpets at Harrods Ltd

S3, Episode2: The Empire at Home

Ana Baeza Ruiz talks to Deborah Sugg Ryan and Sarah Cheang about how the British Empire shaped our everyday experiences of home.

Podcast Transcript

Sarah Cheang is Head of Programme for the V&A Museum/RCA History of Design (MA, MPhil, PhD) in London. Her research and teaching focuses on East Asian fashion history, gender and the body, with a special interest in fashion exchanges between China and Britain, and on fashion, race and cultural expression.

Deborah Sugg Ryan is Professor of Design History and Theory at the University of Portsmouth. Author of Ideal Homes: Uncovering the History and Design of the Interwar Home (Manchester University Press), she is currently writing a book on the history of the kitchen for Reaktion. She is series consultant historian and a presenter for the BBC Two television series A House Through Time and also wrote and presented Trading Spaces for BBC Radio 4, and has contributed to many other programmes.

Welcome to That Feels Like Home, a podcast by the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, reaching you from Middlesex University London. I’m Ana Baeza Ruiz, and I’m hosting this third series to look afresh at what ‘home’ is, and what it means.

We’ve previously looked at home from a wide range of perspectives, including in series 2 some of our shared experiences of home during the pandemic. This season, we’ll be in conversation with academics and activists who have moved beyond traditional ideas of home as a place ‘of safety, privacy, and care’.

Each episode will propose alternative readings of home, from its engagements with histories of empire, the politics of micro-living under neoliberalism, home as a queer space, or the changing meanings of home for people who cross borders.

As always, we draw inspiration from our collections, and the stories missing in them, to rethink the past through the lens of the present.

Ana: In this episode we’ll be looking at how the British empire shaped everyday life at home through products, design and material culture from former colonies overseas.

British homes are connected to imperial histories and geographies. At the height of British colonialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, practices of domesticity and homemaking were shaped by new patterns of global consumption. And in this episode, we’re going to look at some of the ways in which discourses of the British Empire, and nation, were reproduced in British homes through domestic practices. Starting from MODA’s collections, we’ll talk about the sale and home display of embroideries from China, of exotic goods in department stores like Liberty’s or the Impact of Empire on suburban life. And we’ll think about how homemaking has connected these ideas about the household to ideas about the nation and empire. Of course, the influence of empire on ordinary life was uneven. So we’re only going to be able to cover a small part of the story. But I’m so excited to be joined today by Professor Deborah Sugg Ryan and Dr Sarah Cheang. Welcome, Deborah and Sarah. It’s great to have you here.

Deborah: Hi.

Sarah: Thank you for inviting us.

Ana: And so I’d like to start by thinking about these concepts and ideas of the English home and the domestic, and there’s a book recently published by the historian Laura Humphreys just a few months ago that talks about some of these issues (Globalising Housework). And I’m quoting from the book.

She says: “The English home, regardless of its location, has always been a political global space”. So I wanted to start with this quote, just to begin to disentangle two things. The first is, when can we start thinking about this idea of the English home, that is, domesticity is something that is associated with Englishness that’s framed through the lens of national identity. And then secondly, there is this question of how that Englishness is being formed in relation to an outside, to what is perceived as non-English, as a foreign other. Can you speak a little bit about this, Sarah? Would you like to go first?

Sarah: OK, well, I’m going to start with the second part of that question and really with an observation that although England is part of an island, we’ve hardly been cut off from the world. And the more that the English have gone out into the world, especially through colonial history, the more the world’s been invited back into the English home, you know, through travel and trade, souvenirs, gifts, imitations of other cultures, that kind of thing.

So the great thing about studying the material culture of the home is that enables you to subvert some of those political and ideological stances that you encounter about what Englishness is. You know, no matter what kind of nationalist rhetoric about Englishness that we’re dealing with, this sense of domesticity, when you actually look at what people had in their homes was being created from objects and designs from all over the world. So this is a domesticity that reflects a range of relationships with the global. I’m thinking of rugs and ornaments and so on, that produce an English position in relation to the rest of the world, not apart from it. It’s all about English interactions with the world.

Ana: Thanks, Sarah, and we’re going to get into talking about some of the details of those um objects in the home a lot more later. But, Deborah, would you like to say something about that first part of the question in this kind of trope of Englishness and domesticity and how you’ve looked at it?

Deborah: Yeah, I mean my work has been focused on the 20th century, particularly the interwar period. And I think what is particularly interesting about that period is that there is a kind of sense of the inevitability of the decline of Empire. So there’s a kind of last gasp of empire. But the histories of Britain and Empire are still absolutely inextricably intertwined, as Sarah said. And I think one of the things that is really interesting is that kind of constant exchange between um, Britain and the Empire because if we if we think about the average family, most people have some kind of a connection with Empire, with the colonies through their families. It could be through something like service in the armed forces. Lots of people worked for companies which traded with parts of the British Empire.

And also lots of people had direct experience of the empire through emigration as well. And I think this is something that has been a little bit kind of underplayed. Um, I had a quick look at some of the statistics in advance of this and in 1923, over a quarter of a million British people emigrated to the colonies. And I think this is quite an extraordinary statistic. And then you get those people coming back as well. So you get this this kind of sense of an imagined England by the people who remake home in the Empire and then a kind of another imagining when they when they come back as well. And of course, this is also a route for objects coming into the home as well.

Ana: Thanks Deborah, what you’re saying also makes me think about, some of the debates that have been going on amongst historians about the impact of Empire on ordinary and everyday life, I wonder if you-have something more you would like to say about that connection between of ordinary life and Empire?

Sarah: Yeah, I mean, I would also like to speak about what ordinary Englishness looks like. I’m English and I’m of mixed heritage. Half my family are Chinese, so immigrant English histories are also a really potent place to think about, I don’t know English versus British, as well as English versus Empire out there.

Deborah: Yeah, I mean, that’s the term that I use in my book, is I talk about the detritus of Empire being washed up in the home, which is a term that Paul Gilroy uses in The Black Atlantic, which I think is just really useful and kind of deeply resonant as well. And in some ways that maybe some things that that were seemingly exotic and foreign in origin just become so familiar to us that they become part of home. So I’m quite fascinated by that kind of everyday imperial and exotic in the home and the kind of objects that become part of a kind of peculiarly English sense of taste. And, you know, we can see them scattered through MoDA’s Collections, particularly in the trade catalogues. So you’ve got things like ebony elephants, oriental rugs, Benares brass work and all of those things are coming into the home through different means, sometimes as gifts, through family members or things that that people kind of brought back. But also they could be purchased as well in department stores.

So you don’t necessarily have to have that family connection to have those things in your home. And of course, this had been happening for hundreds of years. You know, as Sarah says, we weren’t cut off, we were a seafaring nation. And I think it’s that sense as well of this kind of peculiarly English identity and as kind of seafaring conquering nation that rules the waves that that gets evoked a lot in these ideas of Empire.

Sarah: Yeah. And I love the way you’re talking about detritus of empire being washed up in the home and all these different ways that things come into the home. In my own work, I’ve written about this using terms like flotsam and jetsam, because there’s also something often forgotten about how these things have come into the home. And it’s part of how they then become really English that you’ve got these things that your grandmother or your great grandmother bought or even your mother. And the stories have been lost or it’s just always been in the family and it becomes so central to the domestic interior and to childhood memories and so on. And it is like something washed up on the shore. Nobody really knows who it was or how it got there. And then they move around and then someone dies and it all goes to a junk shop and then it all this cycle begins again. I’m fascinated by the way that things are handed down and the way that stories and ideas get attached to them, particularly stories about travel, but also how those stories get lost or reinvented.

Deborah: Mmm I think that’s really interesting and one of the sources that I’ve looked at are the Mass Observation mantelpiece surveys, which are just a really brilliant insight into the kind of things that people accumulate. And they talk about ornaments on the mantelpiece, it’s is a survey that got repeated several times. But in 1937, after dogs and cats, the most common ornaments to found on the mantelpiece was an elephant. And of course, elephants have this kind of hugely resonant, as a as a sign of empire because, you know, we’ve got them coming from different continents, different types of elephants and different places. And what’s really interesting in the Mass Observation survey is you get you get the diarists recording where these elephants come from and the different types of elephants. Are they ebony? Are they teak? Are they from Ceylon? Are they from Burma? Where have they come from, who have they come from? So, as Sarah says, these objects kind of encapsulate family stories, but of course, these disappear as our memories fade.

Ana: On that note, I wanted to ask you about, the impact of imperial trade on domestic interiors. You’ve been talking about how these objects capture the memories of families. But I wanted to have a sense of how these commodities are travelling and how they actually come to Britain and Sarah, you’ve particularly looked at Chinese products as a source of Chinese imagery in the West. So could you speak about some specific objects that are making their way into Britain and how they’re shaping the British interior.

Sarah: There’s so much there in that question. Design historians often start with the great exhibition of 1851. It’s this key moment, and one of the reasons it’s a key moment is that you’ve got all this ephemera, all this reporting of the exhibition, all these images, drawings, accounts and catalogues of what was there. So it’s a really easy point for historians to pinpoint Chinese objects in the case of my work coming into Britain. But actually, what does it really tell you? It tells you what a group of British traders were able to get their hands on in China at that time. It doesn’t tell us anything about what the Chinese wanted to sell to Britain, but it certainly tells us what a particular group of British traders wanted to buy from China. And it shows us how those things could be put together in order to create perhaps – it’s almost like a serving suggestion, isn’t it – It’s an idea of how these things might make might be relevant to your own home. If you’re if you’re an English visitor and if you’re a foreign visitors to the exhibition, it’s showing you what the British have or what the British have access to in China.

So it’s really loaded with the power relations of imperial history, certainly. And it’s really echoing what the British are wanting to buy to put in their homes. So one particular example, which is actually also a very complex example, is the embroidered shawl. So these are beautiful, huge pieces of crepe silk textile that have got this gorgeous, dense Chinese embroidery on them and these very long fringes. Now, these were actually created for the Spanish market originally. So they come out of a Spanish trade with China that predates some of the British trading in many respects. And the Spanish were creating these embroidered garments that would become part of Spanish identity. So they spread throughout Spain and they’re copied in Spain. They’re going into Spain via Seville. And there’s a silk embroidery industry in southern Spain too, so then you get copying of the shawls. And they buy that certainly by the 1920s, they are really powerful symbol of Spanish identity. And for a century before that, they’ve also been a very powerful symbol of Spanish colonial cultures more widely. So we can also think about Latin America and the role of the shawl there.

Now, why am I talking about this in relation to China and the Great Exhibition? Because if you look actually at what’s in the Great Exhibition, these Chinese-made shawls which are covered in Chinese motifs, don’t appear in the Spanish section. They actually appear in the Chinese section of the exhibition. And they were a different kind of shawl, there were these white on white shawls, for example. So you can see how the Chinese are making different product for the British market. And they are vying for a market with the Indian shawl. So the other thing I’m saying here is that there are particular products being produced in India, cashmere shawl, for example, and which are also which become the paisley shawl in the British context. And you can’t really separate out the way these Chinese things come into British space, you can’t separate it out from these wider global interactions and from these really complex trading networks and the power relations that come with them. They will come on the back of military conflict and they come on the back of all kinds of unequal treaties that have been signed and so forth.

Now, the even more complex thing about these shawls is that once you’re into the 1920s, they become incredibly fashionable in England. And depending on the context, you could look at them and say that they were either Chinese shawl or Spanish shawl, you have women wearing these, calling them alternately Chinese or Spanish. So even the question of what is a Chinese thing in British domestic space is very complex. These are the shawls that are often called piano shawls. So you see them draped over objects, you’d seen them draped over furniture. They’re very big. You see them draped over sofas. You also see them draped over women so that they’re very powerful objects in terms of expressing your fashionable identity and the identity of the household. They cross-over between body and furniture and in domestic interior and fashion constantly.

And they also cross over in terms of the imagining of what Chineseness is and even what Spanishness is. I’m pointing here to how difficult it is to pin things down.

Deborah: I think one of the things that really interests me about the way in which goods come into the home is you know, we’ve already talked about family networks, but we could also think about what you could buy in the shops. So if you look at something like the Army and Navy stores catalogues of which MoDA has some great examples, just on a single page, you’ll get this kind of huge coming together of different types of objects from different places. One of the examples I use in my book has an ebony elephant, but it also has Chinese ginger jars and examples of rattan and wicker baskets.

So you could go out and buy this stuff in the shops as well. Another really interesting example that that I came across is um Clifton Reynolds who was quite an extraordinary character, married to Nancie Clifton Reynolds, domestic advice writer. But he had had a career as a kind of salesman, but in a kind of really interesting way. So he talks in his memoirs about assembling a whole variety of exotic goods. And that that raises questions about where did he get them? What if you look at something like the catalogues to the British Industries Fair, that gives you a fairly good idea of what was on offer.

So he is kind of acquiring goods through wholesale means and then he will set himself up in a town with his own showroom and sell directly to the public. And it’s this similar complete mishmash of stuff from India, from Africa, from China, from Japan, all kind of lumped together to give this sort of sense of the exotic.

The other thing I found really interesting when I was doing research for the book was trawling through some of the trade catalogues from the period. And the other thing that you get, you get coming, because obviously we’ve talked about the Great Exhibition and we’re talking about that kind of period of mass production is you get these companies setting themselves up to manufacture at home. So you’ll get imitations of Benares brass work being knocked off in a factory in Birmingham. So you’re getting this this sort of; you’re not necessarily getting the authentic goods from the country of origin, just like there’s a huge market for reproduction old English furniture. You’re also getting this with these kind of imperial goods as well.

Sarah: Yeah, and then you get the need for adverts that say “straight off the boat from Canton” or some such wording like that in order to try and convince the reader that, no, these are real. They’re not the ones that were made down the road.

Department stores, exhibitions and empire

Ana: You’re listening to That Feels Like Home, a podcast from the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, Middlesex University. I’m Ana Baeza, and in this episode I’m talking to Deborah Sugg Ryan and Sarah Cheang about the ways that the British imperial trade shaped everyday life in British homes.As imperial products were made available to consumers through department stores and other stock houses they filled domestic interiors, as we discuss next. They also shaped ideas about life in the expanding suburbs, stay with us for more on this, and how it relates to teaching design history today..

Ana: I wanted to ask you also about department stores. Department stores are a crucial institution also for making global products increasingly available to the middle classes. And there’s one particular one Liberty’s company founded in 1875 that is very well represented in the collections of MoDA. There’s a whole range of brochures and catalogues, with gifts that include Japanese kimonos, lacquer trays, Oriental rugs. And so and there’s something additionally interesting with Liberty’s, which is the then in the 1920s, it’s rebuilt in a Tudorbethan Style. So it’s sort of revival nostalgia of the Elizabethan period. So there’s something quite interesting going on here between, on the one hand, this kind of exterior that is presenting the ideas of nostalgia for a past of Britain, but then also the inside being full with this, imperial modernity. Could you speak a bit about this, twofold qualities of Liberty’s as a particular institution and also the broader role of department stores in this period, for shaping these imaginaries what is outside of Britain and what is within empire.

Sarah: Yeah, well, for me, the Tudorbethan remodelling of Liberty’s in London is part of an attempt to bring other times, as well as other spaces, into the experience of modernity. And it’s also very closely tied for me to the experience of nostalgia and the need for nostalgia as an essential part of what it is to feel modern or to experience modernity. That part of being modern is feeling sad about what you’ve lost in becoming modern. And why did you find that comfort? Where do you find that that thing you’ve lost? Well, in Liberty’s, you see it perhaps in the spaces like the Oriental bazaar that they created. So they have a space, as you’ve been describing and as Deborah has been saying, with all these different things put together, the Benares bronzes and the Japanese dolls and the little pieces of ceramic and all kinds of objects, all put together to create a bizarre effect, which people write about in terms of visiting another country. They write about as if they’ve been on an exotic tour.

Sarah: And on the other hand, we have this reaching back into history and the framing of the modern department store as a Tudorbethan building, I think is very fascinating. And that Tudorbethan building was connected to the other part of Liberty’s which was remodelled at that time, which was a much more of a kind of standard 1920s, 30s piece of modernist imperial architecture.

I also think that there’s a lot of emphasis we can place on Liberty’s. And they’re certainly doing incredible things to promote Chinese objects and constantly trying to do many things to promote the idea that Chinese objects are very genuinely Chinese, not made down the road in the way and but they’re actually coming straight, either straight from China, from the hands of the artisans, or they’re cut from antique Chinese objects. So we have a range of in catalogues from the nineteen twenties, you can see a range of bric-a-brac glove boxes, um blotting books, cigarette containers, the things of putting makeup in, and they’ve taken old Chinese embroidered garments and cut them up and then appliqued those pieces of embroidery onto these objects. So you see this kind of thing going on as a guarantee of proper Chinese objects that you can have in your home.

But at the same time, I think we have to remember that there are shops up and down the breadth of the land where you can buy Chinese things, as Deborah has been saying. And we put a lot of emphasis on Liberty’s because it’s got the big buildings in London; because we can still look at the catalogues (and, you know, we have many of them in your collections); because their garments have got a label on that say Liberty’s. But fancy goods stores, drapers up and down Britain were also selling these kinds of things to a greater or lesser extent. I did a close study of the shops in the town of Brighton, on the south coast between 1890 and 1940, and by looking at newspaper articles, by looking at street directories, by looking at photographs, I could see that there’s a constant supply of this, let’s say, exotic goods from the Empire. And they pop up all over the place in the guise of fancy goods stores and gift shops and drapers and so on. So although Liberty’s is really important, I think there’s always room to think more broadly about this and to remember that Liberty’s is – is it the cream of the crop? Is it the tip of the iceberg? I’m not sure what the right metaphor is, but there’s so much more here, if we can scratch the surface.

Deborah: Yeah, I would really second that because I think, you know, Liberty’s is really appealing for a certain kind of middle class consumer who is educated in a certain way into particular kinds of tastes. But certainly, as Sarah said, this is appearing up and down the land. The example I gave you earlier from Clifton Reynolds, he particularly talks about setting up shop in Wolverhampton, you know, and in a pretty standard industrial town in the West Midlands. So I think this taste for the exotic is there at all price points. And I think that that is really important. I think it takes different forms and, you know, maybe lower down the social scale people are buying the stuff that has been knocked out from factories in Birmingham. But it it’s certainly there.

I mean, the other thing I’ve done a great deal of work on is the history of the Daily Mail Ideal Home exhibition founded in 1908. It’s still in existence and it’s coming back I’m told. Um, the longest continuously running exhibition in the world. And the great thing about the Ideal Home exhibition, it’s a kind of window into popular taste and the exotic is there from the beginning from the very first Ideal Home exhibition. And actually the display of the exotic as appropriated from other international exhibitions, so including allegedly foreign peoples on display, just like you, you get in the villages associated with the various imperial exhibitions going right up to the to the 38 Glasgow exhibition.

Sometimes I think the obsession in British design history with modernism and good design and the role of the state has just obscured so much of what was there. And I think one of the things that is really revealing is that if you open up the pages of something like the Army and Navy stores catalogue or Home and Colonial Stores or one of the furniture retailers (there’s a great catalogue in the MoDA collection by a retailer called Storeys), and what you see is a whole variety of stuff in different styles, both modern – and I use that word, very advisedly as meaning up-to-date new, rather than modernist – and traditional antique reproduction, Old English, Jacobean, Queen Anne, and the retailers are out there to make a profit. They’re not signed up to a particular ideology. And this is what you typically get in people’s homes as well, as you don’t necessarily get somebody whole heartedly adopting one style. You get this kind of mixture. And in the period I’ve done the most work on in the interwar home, you will often get this this mixture of kind of Jacobethan Jacobean Elizabethan combined in something like the dining room and the sitting room parlour, whatever you want to call it.

There are some great brochures in the MoDA collection of estate agents’ show houses, and you’ll often get this mixture of things and completely different styles from completely different periods next to each other. And to our eyes, now, that might seem quite contradictory, but actually it’s not at all to those contemporary eyes, you know, this this idea that you have to decorate in a single style of a single period. That’s not how we acquire things. We’ve talked already about the ways in which things come into our homes. You know, we all have that object that that we perhaps don’t really like. But someone gave it to us and it doesn’t really fit the rest of our decor, but we’ve maybe got um an attachment to it. In my house the argument is over an oak bureau that I really, really dislike. and it doesn’t match the rest of my mid century furniture. But there is no way on earth my other half is getting rid of that because it’s an inherited piece of furniture that has lots of stories and is a reminder of his grandmother and has all sorts of things attached to it. So every now and then I, I look at it and I kind of sigh and say very pointedly, maybe you’ve got space for that somewhere else. But, you know, it’s staying where it where it is.

And I think this is the way in which we live. And one of the issues for me as a historian is I think often historians have been quite seduced by the sources. So when we look at the pictures of room sets that we can find in the historical record, often what we’re looking at are the trade catalogues, perhaps a photograph of a room set in a department store, that maybe it is often a bit more kind of stylistically coherent and doesn’t really reflect the way in which we live and the way in which we acquire objects through time.

So I think it is really easy for us to make assumptions of historians. And what we have to do is to try and somehow get some other sources that help us break down some of that so that what we’re not relying on is this kind of idealized room set of the sort that museums often reconstruct, which bear much more reality to, to the kind of selling interior of the exhibition or department store display than of the ordinary people’s living room.

Sarah: Oh, absolutely, and I love your list of what objects do as well and how we could use them to think differently about- and challenge these histories that come from the objects set rather than the lived realities. I was thinking, as you were speaking, that objects have agency as well. They have a certain power over us, in the story that you were telling. And hah, I was thinking of my, we have a vase which is known as Granny’s vase. And it’s Granny’s vase which came originally from Singapore, but the thing about Granny’s vase is that it’s really delicate. So you spend your whole life trying to protect Granny’s vase. Whether or not you like it, you have to protect it and look after it. And it’s fragile. And it does make you think differently about what people’s motivations and priorities might be and also just how they lived with these objects from Empire.

Imperial images in/of the suburbs

Ana: In this episode I’m talking with Deborah Sugg Ryan and Sarah Cheang about the influence of British imperial expansion on domestic life.

Ana: I would like to maybe also bring this a bit back to the question of Empire and some of the promotional material, at MoDA, particularly one brochure of the firm New Ideal Homesteads that has this image of a married couple that will move into the new house, but they are presented as colonial settlers. So there is all this promotional material particularly in the interwar period about the future residents in the suburbs, and also the images of home. How far do you think that lived up to the reality and particularly, thinking about Empire, the imperial resonances in the suburban home?

Deborah: I talk about that image from the New Ideal Homestead’s brochure in my book. And it’s quite extraordinary they’re represented a bit like kind of American pioneer colonists. And there is this there are these really interesting imperial metaphors when suburbia expands and emerges. And there is this idea that the metropolis is the center and people are going out to found these new colonies in the suburbs. And some of the eyewitness accounts to some extent back this up, particularly when people are going out to new suburbs that don’t have much in the way of infrastructure. There’s this idea of suburban neurosis that becomes a thing that women are diagnosed with in the interwar years because of this this sort of loneliness of being distant from family and friends and traditional communities. And particularly if you get that kind of speculative development that doesn’t have amenities like community centers, sports facilities those kinds of things. So there is this really interesting sort of metaphor of the colonial settler that is imposed on the on the sort of building of suburbia and that idea of the pioneer.

But interestingly, I think in later periods or well, not necessarily later periods, there’s also as well this other thing that that is imposed on the poor in the cities, particularly the through those anxieties around slums and some of the ideas of slum clearance, that you get that idea of darkest England. And you get that idea of this sort of social exploration into the homes that also become this this sort of “other” layered upon it with ideas about race that we would find very objectionable now. But the idea of the lower classes belonging to this inferior degenerate race with these very kind of interesting parallels, and you could look at something like the work of a photographer like John Thompson that that was documenting the slum dwelling poor in London, but also going and documenting other peoples in places like China. And you get this kind of drawing together of these sort of parallels of Empire imposed on the slum dwelling poor as well. So those imperial metaphors work in slightly different ways, depending on whether you’re in the suburbs or in the city slums.

Sarah: I was just thinking about, as well as people going out to Empire, there’s the existence of bodies like the- Is it the Empire Marketing Board?

Deborah: Yeah, that’s right. Yeah.

Sarah: So you’ve got this the Empire Marketing Board who are there to convince everyone to buy the British Empire goods. And it reminds me of Deborah’s phrase about the last gasp of Empire. So isn’t that the last gasp, isn’t it a bit of a lost cause if you’ve got to start trying to advertise, to convince people to buy the goods that you’re using to try and prop up the whole economics of the British Empire at the same time as those strategies are clearly actively trying to encourage people to bring more goods from the Empire back into the English domestic home.

Another thing I want to mention, actually, was missionaries. Because missionary organizations are constantly sending people out into imperial spaces and beyond the edges of British Empire as well. And these missionaries actually come from quite a very wide range of social positions. So you do get a lot of middle class missionaries, but some of the missionary organizations will also draw from working class communities. And they certainly come back with images and objects and they are intent on connecting with middle and working class communities back in in Britain, to get communities in Britain to appreciate cultures elsewhere and connect with those people elsewhere, and then give money to the missions to convert them to Christianity to save their souls. So this is what they’re doing

And they’re using objects all the time, partly to educate. So they will bring back clothing and all kinds of artefacts. It’s almost like an it’s an ethnographic collection in the sense; all kinds of artefacts that show how society works. They bring these back from India, from China, from Japan, from Korea and so on in order to put on lectures and to put on exhibitions as well, to educate people. But more than that, they are also selling these objects to raise money for the mission. So they set up workshops in, for example, China, where the local people get an income, they learn a trade or they learn a skill. And then those things are sold back in Britain and elsewhere to raise money for the missions. And this is another way in which things are coming into Britain, coming into the British home. That’s not the same as talking about Liberty’s. And I think also enables you to think about a lot of different kinds of income brackets and all class positions.

Decolonising design history

Ana: You’re listening to That Feels Like Home, with me Ana Baeza. After talking with Deborah and Sarah about some of the ways in which objects from the British Empire made their way into the ordinary homes, I wanted to hear from them how we can start to tell different stories, and change the way design history reflects on Empire.

Ana: So these ethnographic perspectives of looking at ordinary histories of ordinary homes obviously has a bearing on the kind of historiographical approaches that we take. And I wonder how you see this as part of a wider attempt to reframe design history. And how do you see this connecting to some of the decolonial discussions that have been happening in the last couple of years?

Sarah: I think it’s useful, first of all, to think about the difference between a post-colonial critique of imperial histories and the idea of decolonizing design history or decolonizing the way in which we approach those histories, because I think they are two different things. So one is certainly about deconstructing why and how these imperial images or these ideas about Empire or these ideas about Britishness came about, and how they may have or how in most cases they are highly racist, highly problematic and so on. Whereas a decolonizing approach surely stresses more of a sense of, “OK, so what are we going to do about this?” And how can we having realized that these things are racist, how can we prevent ourselves from continuing to compound the fact by endlessly discussing, drawing attention to, pointing to racism? Actually, what can we do about that? How can we live with it? And how can we respond to the fact that these are incredibly racist histories that we’re dealing with?

And so for me, a lot of the, a lot of the ways in which we’ve been discussing this history, need to really bring in -not just perspectives that haven’t been told before – but to place more emphasis on other ways of talking about objects that come from totally outside of the established way of understanding what a jar is. So if you were to go from the point of view of the Chinese maker of the jar- now there’s a question of how you would do that – but if you were, what kind of thoughts could you have about that jar’s travel into an English domestic space? Another way to think about this is also, as I said earlier, what are we imagining Englishness to be? And is there a place here for Englishness that is not white Englishness, but that is perhaps an immigrant Englishness or is a mixed heritage Englishness?

So these are two possibilities, certainly in terms of what I would see as an actual decolonizing approach. The other thing I’d like to mention is that, well not mentioned but stress, really, is that decolonizing isn’t a thing that you can just do and then it’s done. Decolonising is a process. Decolonizing is an attitude, perhaps, but it’s not really a task that you can do and that’s that, because it’s really about figuring out how you live with colonial histories.

It’s different to the idea of decolonizing in terms of, “OK, we have had a colonial status and now we are going to have a post-colonial status and how do we decolonize our culture?” That’s a different thing. I think the decolonizing we’re talking about here is more of an area around how do we practice, what kind of methodologies do we use? What kind of areas should we focus on next? And how do we prevent ourselves from continuing to reiterate and therefore continue colonial history?

Deborah: Yeah, I mean, I would echo lots of what Sarah has said, and I think the other thing as well is, you know, it’s sometimes very easy to overlook things, edit things out because they don’t fit a narrative. And if we think of design history as a kind of modernist discipline of with a sort of linear narrative around good design, like the famous Alfred J Barr chart in the Museum of Modern Art and the way in which it finds it difficult to think about non Western cultures. I think one of the things I tried really hard to do with my work was to really, really be very mindful and open of the kinds of objects that fills our homes and the problematic ones that didn’t seem to fit. And it’s from that you absolutely see that kind of breadth of stuff that has these imperial and colonial histories and origins, or that is engaging with those ideas.

So, that is maybe one of the things that is very distinctive about design history. And it’s really interesting seeing other historical disciplines, having a sort of material culture and object turn when you come from a discipline that is absolutely founded on that. And that is absolutely at the heart of it. So I think I think one of the things is to not lose sight of the objects themselves. But the thing for me that is very useful is this idea of relationships between objects and people that start, and those multiple relationships, that start helping you to unpick some of those kinds of meanings. And often they’re going to be uncomfortable and difficult as well. And you, know, we often do to have to confront these racist histories and meanings through the absolutely every day.

Ana: thanks so much, Sarah and Deborah, I think we’ve covered so much ground, and it’s as I said at the beginning, this is only a small part of a really big story. it’s been fascinating to speak to you and thanks so much for joining us on the podcast.

Sarah: Thank you.

Deborah:Thank you.

Thank you for listening, and thanks so much to our guests, Deborah Sugg-Ryan and Sarah Cheang, for joining us today, I thought the conversation challenged views on the home and Englishness in important ways, and it’s clear that the household in Britain, through its design of interiors, objects and fashions was a channel for imperial ideas, as we’ve discussed today… in sum, we can’t think of home as being politically or historically neutral.

In the rest of the series we’ll have new guests joining us and bringing yet more critical accounts of home. If you enjoyed this episode, don’t miss the next one, where we’ll be discussing transnational homes, migration and belonging.

I’m Ana Baeza and this podcast is brought to you by the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, Middlesex University. We’ll be back again soon, stay tuned.

Further Reading

Abercrombie, S.P., 1939. The Book of the Modern House. A Panoramic Survey of Contemporary Domestic Design.[By Various Authors.] Edited and Prepared Under the Direction of P. Abercrombie.[With Illustrations.]. Hodder & Stoughton.

Barczewski, S. 2016. Country houses and the British Empire, 1700–1930. Manchester University Press

Barringer, T. & Flynn, T. eds. 1998. Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum. Routledge

Cheang, S., 2018. Fashion, Chinoiserie, and the Transnational: Material Translations between China, Japan and Britain. In Beyond Chinoiserie (pp. 235-267). Brill.

Cheang, S. and Kramer, E., 2017. Fashion and East Asia: Cultural translations and East Asian perspectives. International Journal of Fashion Studies, 4(2), pp.145-155.

Cheang, S. and Suterwalla, S., 2020. Decolonizing the Curriculum? Transformation, Emotion, and Positionality in Teaching. Fashion Theory, 24(6), pp.879-900.

Cheang, S., 2014. Re-imagining the Dragon Robe: China chic in early twentieth-century European fashion. Global Textile Encounters. Oxbow. Web.

Cheang, S., 2006. Women, pets, and imperialism: The British Pekingese dog and nostalgia for old China. Journal of British Studies, 45(2), pp.359-387.

Finn, M. & Smith, K, eds. The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857. UCL Press

Giblin, J., Ramos, I. and Grout, N., 2019. Dismantling the master’s house: Thoughts on representing empire and decolonising museums and public spaces in practice an introduction.

Gilroy, P., 1993. The black Atlantic: Modernity and double consciousness. Verso.

Hall, C. and Rose, S.O. eds., 2006. At home with the empire: metropolitan culture and the imperial world. Cambridge University Press.

Humphreys, L., 2021. Globalising Housework: Domestic Labour in Middle-class London Homes, 1850–1914. Routledge.

Jones, R. 2007. Interiors of empire: Objects, space and identity within the Indian Subcontinent, c. 1800–1947. Manchester University Press

King, A.D. 1984. The Bungalow: The production of a global culture. Routledge and Kegan Paul

Kuchta, T., Semi-Detached Empire: Suburbia and the Colonization of Britain, 1880 to the Present (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2010).

Mackenzie, J.M., ed. 1986. Imperialism and Popular Culture. Manchester University Press.

Mintz, S.W., 1986. Sweetness and power: The place of sugar in modern history. Penguin.

Smith, M., 2020. Decolonizing: The Curriculum, the Museum, and the Mind (pp. 1-240). Vilnius Academy of Arts Press.

Sugg Ryan, D., 2020. Ideal homes: Uncovering the history and design of the interwar house. Manchester University Press

Sugg Ryan, D,.1999, ‘“The man who staged the empire”: remembering Frank Lascelles in Sibford Gower, 1875-2000’ in Material Memories: Design and Evocation, ed. by J. Aynsley, C. Breward & M. Kwint, Berg, Oxford, pp. 159-179

Walvin, J., 1997. A taste of empire, 1600-1800. History Today, 47(1), pp.11-16.

Woodham, J.M., ‘Design and Empire: British Design in the 1920s’, Art History, 3: 2 (June 1980), pp. 229-40.

Credits

Produced by Ana Baeza Ruiz, with guests Deborah Sugg-Ryan and Sarah Cheang

Editing by Zoë Hendon, Ana Baeza Ruiz and Paul Ford Sound

Transcription by Mia Kordova

Music Credits

Say It Again, I’m Listening by Daniel Birch is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial License

Let that Sink In by Lee Rosevere is licensed under Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0)

Would You Change the World by Min-Y-Llan is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License.

Phase 5 by Xylo-Ziko is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License.