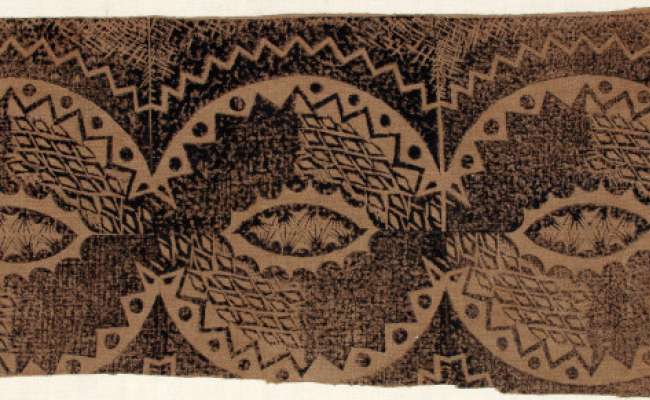

In 1925, Marx began a year-long apprenticeship with fabric designers Barron and Larcher and was still working with them in 1927. She also worked from her own studio designing and printing textiles. In 1926 she received an important commission from Warner textiles, who bought three of her textile designs. And through Phyllis Barron’s sister Muriel, Marx had her first commission for a wallpaper, which was printed with textile blocks.

Marx began to have her work included in exhibitions from the late 1920s onwards, including the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1928 and at the Mansard Gallery in Heals in the early 1930s. This places her firmly within the small coterie of commercial designers receiving attention from the people who mattered (and commissioned) in the London scene at that time.

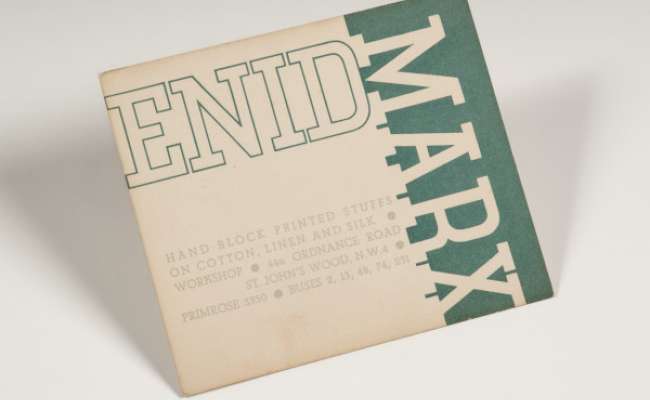

In terms of retailing her textiles, Marx sold through the Little Gallery, Muriel Rose’s ‘lifestyle’ gallery / shop off Sloane Square in London. The Little Gallery stocked Barron and Larcher, and Marx probably established the connection through them. Marx held a solo exhibition there in 1930 but by 1936, finding Muriel Rose difficult to deal with, Marx began to show her work at Dunbar Hay, another shop/gallery.

Design work in wartime

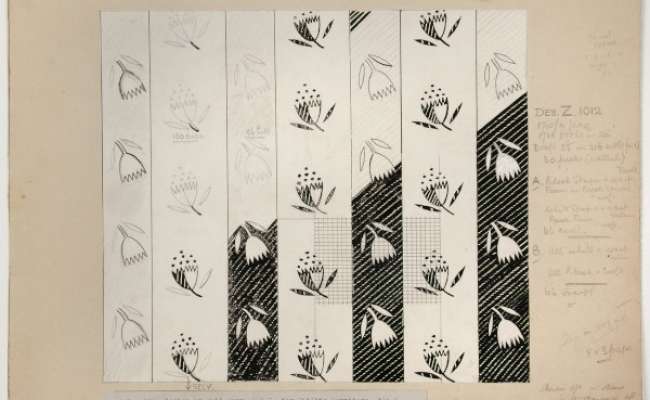

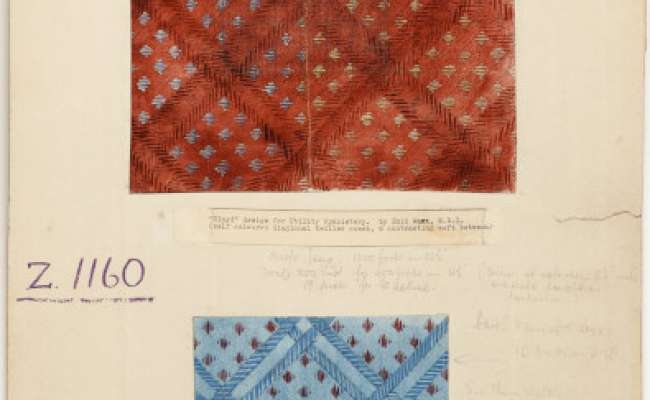

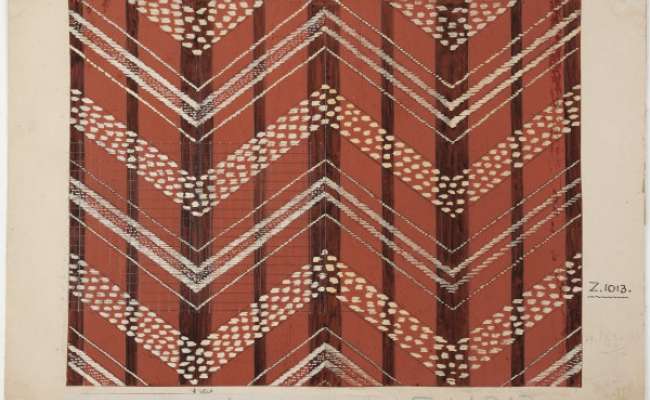

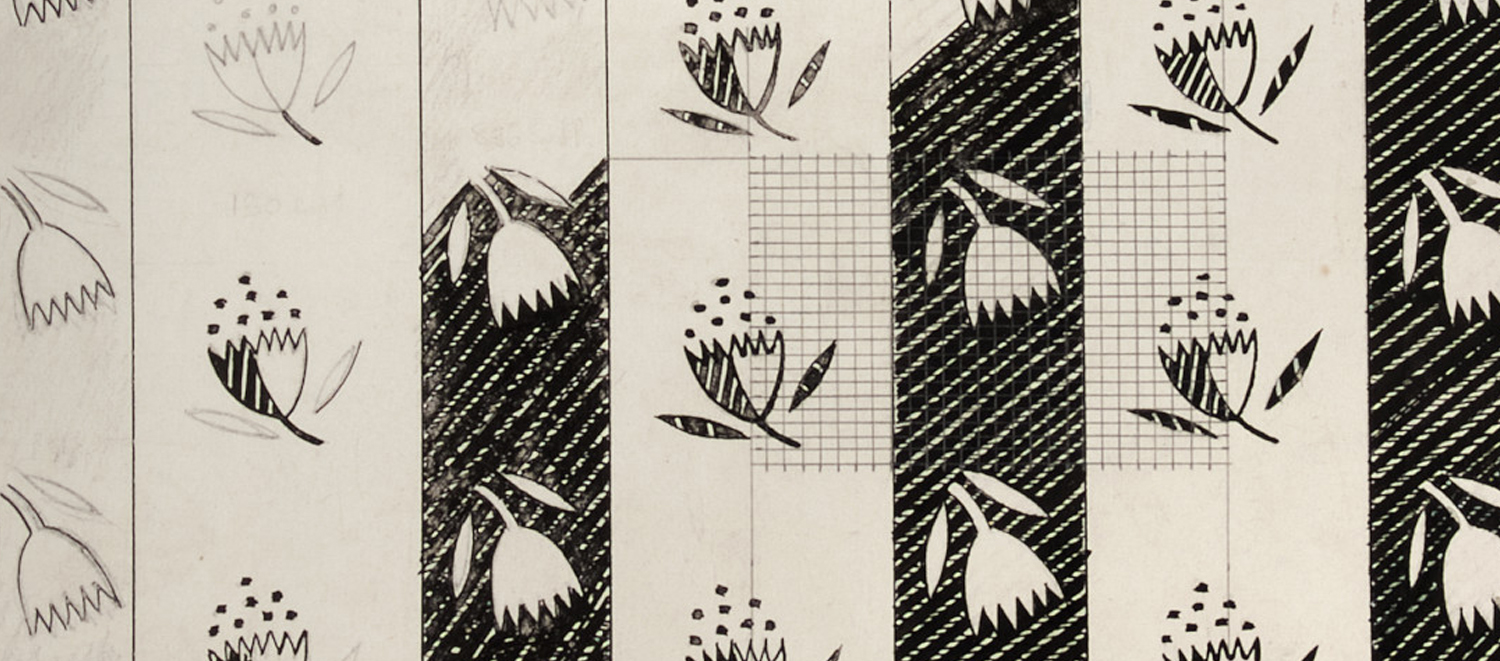

As wartime conditions crept in from 1939, opportunities for commercial designers to work on wartime schemes and propaganda appeared. By 1937 Marx was designing woven textiles, first moquette fabrics for seating in London underground train carriages (along with fellow designers Marion Dorn and Paul Nash) and then textiles for the Utility scheme, run by the Board of Trade. Marx’s first designs for upholstery fabrics appeared in 1944, and she went on to see at least thirty go into production, most produced by Morton Sundour fabrics in Carlisle. Marx’s fabrics were designed with limited resources, under wartime conditions; yet they remain ingenious weave designs, very much in the Scandinavian style, with their own flair and clever repeats.

This period also saw her elected to the Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry and writing an essay about furnishing fabrics in Design ’46, the catalogue that accompanied the Britain can Make It exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1946. She was also becoming more of an advocate for the role of designer in industry, something she was well placed to comment upon.

After the War

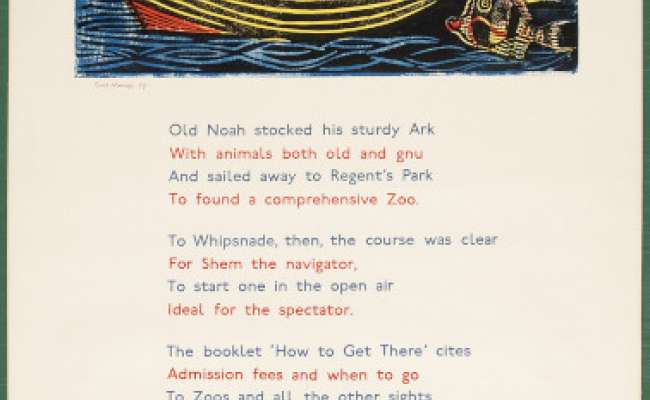

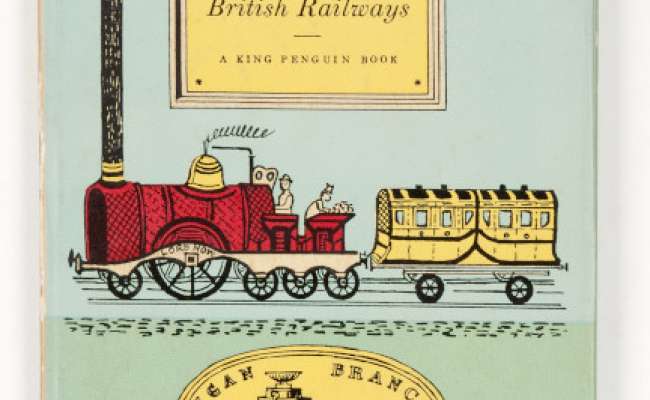

After the war Marx became involved in designing for the export trade, designing prints for the Morton Sundour Company. She also designed some rug and laminate designs. She continued to work on paper throughout her working life making woodcuts, watercolours and linocuts. She worked on many designs for the publishers Chatto and Windus, including patterned covers for their Zodiac Books series from the late 1930s. She produced several children’s books for Faber & Faber, including the wartime-themed Bulgy the Barrage Balloon and The Pigeon Ace. And she did four covers for the King Penguin book series.

Marx’s long interest in popular, or folk, art lead her to produce two books with her friend Margaret Lambert. English Popular and Traditional Art was published by Collins in 1946 and English Popular Art by Batsford in 1951. The two women, who lived together for many years, also collected representative examples of this genre for many years and this collection is now housed at Compton Verney. From Staffordshire pottery figures, to glass paperweights, from naive art to a ship’s figurehead.

A lasting legacy

Post war, Marx was increasingly involved in education, as a lecturer, becoming head of the Department of Dress, Textiles and Ceramics at Croydon School of Art. Marx and Lambert had worked for the Council of Industrial Design in the 1940s, a reforming group of design intellectuals. It was something that Marx remained passionate about until the end of her life; the role of designer in industry was one she had both personal experience of and a reforming zeal for.

In her later years, as well as seeing her beloved collection housed at Compton Verney, Marx saw several retrospective exhibitions on her work held. There was increasing interest from fellow designers, particularly printers and graphic designers who were drawn to her illustration output.

2018 sees a major exhibition and book on Marx at the House of Illustration in London’s Kings Cross. This will surely see her reputation grow, along with values assigned to her work. But it will also serve to educate a wider public on Marx’s work as a designer over so many years, something that would surely have satisfied her most of all.

Jane Audas is a freelance digital producer, writer and curator.