Deborah Sugg Ryan: TV historian publishes new book

You may have seen Professor Deborah Sugg Ryan recently on the BBC2 programme A House Through Time. Deborah appears on the programme and also acted as consultant to the series. She is Professor of Design History and Associate Dean (Research) in the Faculty of Creative and Cultural Industries at University of Portsmouth.

In addition to her TV work, Deborah has a new book coming out in March, entitled Ideal Homes 1918-39: Domestic design and suburban modernism, published by Manchester University Press. She drew extensively on MoDA’s collections in the course of her research.

In this extract from her new book Deborah discusses the home of Marks and Tillie Freedman, in Southgate, North London, which they purchased in 1934. Their decisions around the house purchase are documented in a series of correspondence which were found in a skip in the early 2000s. As Deborah argues, the correspondence between Mr Freedman and the builder reveals that his aspirations to modernity were not always achievable within his budget.

Making modern choices: Marks and Tilly Freedman

The biggest opportunities for householders to be modern in the interwar years came with the purchase of a new house. Builders often allowed purchasers to choose their own fixtures and fittings. It was standard practice for house buyers to be given a budget for decoration (paint and wallpaper) and features such as fireplaces, usually to be spent at the builder’s nominated supplier and then installed as part of the purchase price.

The consumer possibilities offered in the purchase of a new home are vividly illustrated in the following story of a purchase of a semi-detached house at 1 Burleigh Gardens, Southgate in North London in 1934 from the builder, A.T. Rowley of Tottenham, by Marks and Tilly Freedman from Walworth in South East London.

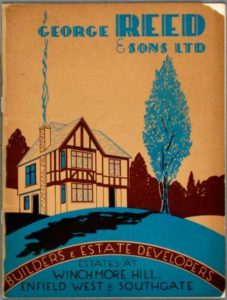

The Freedmans’ new semi-detached house comprised two reception rooms, kitchen, scullery, hall and landing, three bedrooms, a WC and a bathroom. As the first house on its side of the road, it benefited from a large corner plot with gardens extending to the side as well as the front and about 100 feet to the back. Its interior space dimensions were relatively generous. The house had a red tiled roof and bay windows in both front reception room and master bedroom with hanging red titles between them. The façade was built of red brick and rendered on the first floor. Although not half-timbered, it gestured to a Queen Anne historic style. Seen in the broader context of the full range of designs on offer, this was quite a restrained and modern style.

Choosing Modern Decorations

There was extensive correspondence between Marks Freedman and the builder, A.T. Rowley. The Freedmans had considerable freedom in choosing fixtures and decoration for the house. In many instances they exceeded the allowances in the purchase price and paid extra for additional features. For example, they paid £3.3.0 for the fitting of coloured leaded lights to the fanlights on the front elevation.

The Freedmans’ correspondence with the builder reveals their intense desire to make modern choices

The Freedmans’ correspondence with the builder reveals their intense desire to make modern choices, such as an electric point in the bathroom to illuminate a shaving mirror. However, the letter with the quote of twenty-five shillings for the cost of the work was annotated in Marks’ handwriting, ‘phoned them, not required’. Time and time again throughout their correspondence, the Freedmans reined in their consumer desires. They even tried to cut costs by omitting a wardrobe cupboard in a bedroom and picture rails. What is unclear is whether this intense scrutiny of details was a joint enterprise by the Freedmans; all the letters were signed by Marks; Tillie was only mentioned once in the correspondence.

A Modern Fireplace

The Freedman’s relationship with the builder became particularly strained over their choice of fireplaces. The purchase price of the house included the choice and fitting of fires and fireplaces to the value of £20, which could be chosen from Messrs Cakebread Robey of Enfield.

For the two receptions rooms and two of the bedrooms the Freedmans spent a total of £31.8.6. on fireplaces, over 50 per cent more than in the builder’s allowance. By the mid 1930s gas and electric fireplaces became popular with householders who preferred them to coal fires, which were perceived by some as great harbourers of dust and disease. The Freedmans’ choice of the fireplaces for downstairs were particularly modern for the time.

“I am surprised to see that the gas pipe has been carried along the hearth, instead of downwards through the hearth which is of course the correct way”

Mr Freedman wrote to the builder that in the front reception room he wanted ‘Portello 3-unit gas fire with wall panel. Since this has no hearth and is well above the floor, the floorboards should be continued up to the wall and the skirting also continuous, in a similar manner to the illustration in your possession of a Portcullis gas fire’.

Portcullis gas fires were first shown by Bratt, Colbran & Co in the autumn of 1932. The architectural historian and critic Nikolaus Pevsner commented approvingly that the ‘radiants form a grid or gridiron of portcullis shape, an artistic improvement of great consequence’. (Pevsner, Enquiry into Industrial Art, p. 22). Pevsner felt this more preferable to a gas fire that imitated a coal fire flame effect. The portcullis shape increased energy output, as well as being aesthetically pleasing. As Pevsner noted, they were at first ‘too new and unusual to be commercially successful’, and it took at least a year for retailers to stock them let alone the public to purchase them, which suggests that the Freedmans made a progressive and cutting edge choice.

Advertisment for a Portcullis gas fire in Bratt Colbran, Catalogue, c.1935 (BADDA 322)

To his consternation, when the builder installed the fireplaces it was not done to Mr Freedman’s satisfaction and he wrote to complain:

“With regard to the fireplace and gas fire in the back reception room, I am surprised to see that the gas pipe has been carried along the hearth, instead of downwards through the hearth which is of course the correct way as shown in the enclosed leaflet from the makers [sic] catalogue. Seeing that I have spent £13 on this fireplace, it seems a pity that its appearance has been spoilt by the fitting, and I consider that it should be put right.”

There followed a protracted correspondence over who should bear the cost of correcting the placement of the pipe. How typical the Freedmans were of interwar homeowners is hard to ascertain. While I have discussed here their more modern choices they also exercised more traditional tastes in other areas of the house. What does seem clear is that it was possible to select both modern and traditional designs without any apparent contradiction.

As Deborah demonstrates, ‘modernity’ was an idea that had to be negotiated with some difficulty by residents of London’s new suburbs in the 1930s. We look forward to finding out more when the book is published in March.