Ellen Martin: The Value of the Everyday

The following piece is by Ellen Martin, who recently completed an MA in Design and Material Culture at Brighton University.

Illustration of ‘The Dining Room’ in Wates’ ‘Wakefield’ house, exhibited at the Ideal Home Exhibition. 1938. Exhibition catalogue. Wates Guaranteed Houses: Olympia 1938. © MoDA. Object number BADDA4619.

Last year I completed my MA in History of Design and Material Culture at the University of Brighton – and the wonderful collections at the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture (MoDA) were crucial to my research process throughout.

My dissertation – ‘Furnishing Fabrics for the Suburban Home in the South East of England, 1930 – 1939’ – sought to bridge the gap between histories of the ‘ordinary’ suburban home and of textile design in the 1930s. Existing histories of 1930s furnishing textiles have favoured the modern output of pioneering artist-designers and studios, such as Edinburgh Weavers. In reality however, these modish fabrics would have been used to furnish the homes of a fairly wealthy and style-conscious minority!

So how were these modest homes really furnished? What fabrics, patterns and colour palettes really appealed to the new residents of Barnet and Hayes, Edgware and Enfield? Were modern styles adopted, or did loyalty lie with traditional pattern?

Living room interior of Messrs Edmondsons Ltd. show home, furnished by Henry Haysom on the Meadway Estate, Southgate, North London. c. 1930. Photograph. © MoDA. Object number COP3.

Before too long I recognised that mass-produced furnishings sold at lower market levels don’t merit much space in today’s museum archives. It’s a sad fact that designer names take precedence. Existing everyday textiles are particularly difficult to source as they are so perishable. My research would warrant some more shrewd investigation, using secondary sources to build an image of the market.

This is where MoDA’s collections prove so valuable. The ordinary, everyday and indeed domestic are celebrated here! It was through the advertising material, trade catalogues, exhibition catalogues, estate agents’ publicity and domestic photography of the period that I could build more realistic picture of the market. The archive also comprises a fantastic local history resource – one that paints a rich picture of North London’s twentieth century suburbs.

This image is from a promotional brochure made by Wates construction company, who built a huge amount of suburban housing outside London in the 1920s and 30s. They promoted this imagery of newly-built suburbia to prospective buyers – and as can be seen, the curtains here suit the domestic scene – plain and pretty. The frilly pelmets encase leaded casements windows typical of such homes. The image below is a photograph of a suburban show-home.

Cretonnes & Casements’. 1933. Trade catalogue. Hawkins Household Catalogue. © MoDA. Object number BADDA71.

Again, the styling is traditional and typically ‘English’ – damask covers the settee and thin chintz curtains line the windows. In this way, a domestic aesthetic was already constructed, one to which new residents could easily conform. Construction firms even struck deals with local furnishers and advertised their wares in show-homes.

Trade catalogues and advertisements paint a similar picture. This trade brochure from London-based furnishing store Waring & Gillow presents a range of furnishing fabrics to suit a range of budgets. There are no modern styles on offer here – instead, traditional silk damasks, floral printed cretonnes, chintzes and stripes.

Preston-based firm John Hawkins & Sons Ltd. promised to bring ‘the Mills to the Multitude’ with their mass-produced fabrics sold at modest prices. Hawkins specialised in cheap printed curtain and dress fabrics and commissioned designs from the Silver Studio throughout the 1930s. Catering to popular taste, most of their fabrics in this decade were floral, traditional and most importantly, ‘charming’. They often used oranges, browns and beiges popular in the thirties and known as ‘Autumn Tints’.

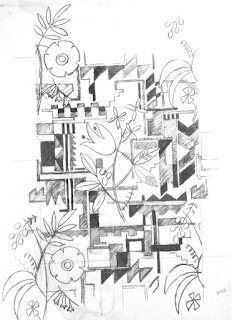

Design for furnishing tapestry by George H. Willis for the Silver Studio. 1932. Charcoal on tracing paper. 64 x 47.5 cm. © MoDA. Object number SD1898.

As can be seen, abstract and geometric shapes were incorporated into floral design in an attempt to adopt the modern trend. This diluted fusion of styles became known (often disparagingly) as ‘modernistic’. It is also interesting to compare some of the Silver Studio’s designs for similar furnishing fabrics from this period. The design below, for example, designed by George H. Willis in 1932, also combines angular shapes with more palatable floral sprays.

These examples just touch the surface, but MoDA’s collections offer the design historian valuable insight, not only into the designer’s world but the consumer’s too. What I think is important, is that these objects testify to popular taste, rather than just the cultivated and cultured.

Hi, this is great patter design and really like it. Thanks for share with us nice post and information that will useful for us.