Catherine Rose Scott: Musings of a Wallpaper Rookie

I can’t claim to understand wallpaper very well. Even though I know that it is durable and has an impressive variety of patterns, the idea of essentially glueing paper to a wall is alien to me. Maybe this comes from growing up in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, where wallpaper had fallen completely out of fashion by the time I was born. To my friends and me, it was just a word in the dictionary, at which we might have glanced while looking for more interesting terms like “Walpurgis night” and “walrus moustache”.

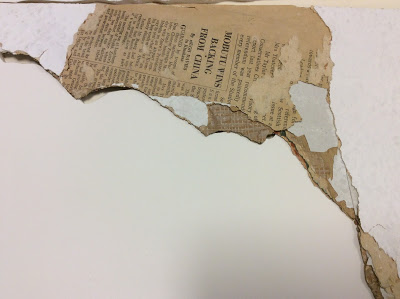

With this in mind, I stand in the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, holding a wallpaper ‘sandwich’, as its label tells me. ‘Sandwich’ is a fitting word for the twelve-layered chunk of wallpaper, ripped from a dormitory wall of Peterhouse Cambridge, the oldest college of the university. After accumulating layers for over two hundred years, the piece was removed during renovation in 2001 and donated to the museum two years later. Today, it smells sharply of decayed starch, like a great-grandmother’s old house. It is brittle, and I must take care when handling its jagged edges.

For more specific information, I must look at a box of separated layers. Each sheet has been covered with a plastic sleeve and labelled, with approximate dates, styles and production quality. The oldest layer is described as handmade paper from the late eighteenth century, while some can be given even more specific information, particularly ‘Mallow’, a blue and cream floral pattern designed by Kate Faulkner in 1879. For many years, a series of college students over the years had moved into a room and decorated it to their tastes. Looking at the sandwich, I know that these twelve people came from different backgrounds and eras. Some chose cheap, low quality paper while others could afford the finer, more exclusive varieties. I find the layer with a lattice of ivy leaves dating from 1905 to 1920 particularly attractive. Even after a century, the pattern’s detail still evokes the feeling of touching smooth, cool ivy leaves.

The final layer is unlike the others: plain white wood-chip paper supposedly popular in the late twentieth century. I find it coarse and uninviting, like a hastily primed canvas. Even if it was fashionable for its time, it feels more like a mask covering the rich history beneath it.

Fortunately, the mask didn’t work, and the many layers once again get to see the light of day. They could have been discarded without a second thought, but somebody recognised them as pieces of mankind’s history.

Not all of the wallpaper layers are equally visible. Some can just barely be seen, and looking at them is much like peering through tiny windows into the lives of their owners. This comparison to windows occurs to me specifically because I am also looking through a window into a fashion that I had missed completely. I might not be familiar the purpose of wallpaper, but what I can see is a physical record of the evolution of our culture. This fragile chunk of processed plant matter in my hand is a microcosm of society.

Perhaps my new understanding of wallpaper jumps to too many abstract conclusions, and maybe it is just a quick fix to hide cracks in your wall. But even if I won’t be plastering it over my walls in the near future, I am happy to be holding this wallpaper sandwich. I can do this because we humans, with our libraries and museums, are creatures with an urge to chronicle our time on earth. It has outlived many fashions and even some of its owners, and it is satisfying to know that it is getting the respect that it deserves.

Catherine reflects on the writing process

While writing this piece, I realised that my stories about everyday objects can be more than meaningless trivia. One’s thoughts about something mundane can, with the right words, be engaging to others. I probably knew this already, but this project left me feeling vindicated.